It's open season for insect pests

FREE Catholic Classes

McClatchy Newspapers (MCT) - The Insect in Winter might not make a catchy, Oscar-winning film title, but for gardeners, it's an important and timely topic.

Highlights

McClatchy Newspapers (www.mctdirect.com)

1/28/2009 (1 decade ago)

Published in Home & Food

Winter presents an opportunity to eradicate certain pests while they're hunkered down in small, compact egg masses. You can nip hundreds of them with a single snip before buds break open in the spring.

Masters of camouflage, insects create casings that blend into your landscape trees and shrubs, hidden in plain sight. But if you know what to look for, and which greenery is affected, you'll begin to notice and recognize them. So grab your pocket knife or clippers, because we're going on a bug hunt.

Three structures that I like to think of as "I see you" finds are so common in the landscape that you probably can discover them within a block of your home. A fun activity for your neighborhood association might be to organize a treasure hunt to see who can locate them the most quickly. It shouldn't take long.

First are the egg masses of the Eastern tent caterpillar, which look like puffy half-inch wide bands of dark-brown foam, about a foot from the tips of twigs on fruit trees and shrubs that are in the rose family. These include ornamental crab apple and wild cherry trees, and the flowering quince. Covered with a shiny varnish called spumaline, they each can contain eggs of about 400 potential caterpillars, which hatch in early spring as leaves begin to unfurl. They go on to devour greenery and build weblike nests in the Y-shaped joints of tree branches.

Insects undergo a metamorphosis throughout the year, changing forms during their life cycles. These masters of survival transform from eggs to hungry caterpillars, then to pupae and finally to egg-laying moths. Why not simply snip off and destroy the egg masses now? Howard Murphy, who has maintained his home landscape in wooded farmland off Delaney Ferry Road in Woodford County, Ky., for about 40 years, recommends this simple way to prevent the insects from defoliating trees.

His diligence has paid off.

"Obviously, this technique is only effective for control of those masses within reach, but I will gladly reduce the number to that extent," he says. On the other hand, he doesn't touch the frothyÂlooking beige egg cases of praying mantis on his clematis vines. Those beneficial insects get to see spring.

Another fascinating overwintering structure is created by bagworms, which are the larval form of a type of clear-winged moth. Their 2-inch egg cases, found in evergreens including spruce, pine and juniper, hang suspended from branches like earthy holiday ornaments. You might think they are misshapen pine cones or a broken brown twig bristle. They're intricate patchwork bags ornamented with bits and pieces from the host tree, and they're made with silk spun by a single caterpillar that lives inside its bag most of its life.

The eggs, which survive inside the female's body in the bag, begin hatching in late May, when the tiny bagworms emerge from an opening at the bag's bottom to hang from silken threads that will be blown and dispersed by the wind.

University of Kentucky College of Agriculture entomology professor Daniel Potter describes them as "little ninjas," and he advises not only removing and destroying the bags from trees in your yard before they can hatch, but also checking your upwind neighbors' yards for infestations. Left uncontrolled, they'll defoliate your tree, eventually leaving it too weak to survive.

The third structure is a deformity caused by the horned oak gall wasp. The galls are easy to see when leaves have fallen for the winter and bare tree branches are silhouetted against the sky. They are most often present where there is a monoculture of oak trees. The pithy galls, which look like a series of toasted, somewhat prickly marshmallows lining the branches, are nutrient reservoirs for the eggs and larvae of this wasp.

If left undisturbed for five to 10 years, they can proliferate, weighing down branches to create a "weeping oak" effect and causing dieback. What to do? As soon as you notice one or two galls in your trees, remove them. Once again, action and awareness can prevent a major problem of exponential growth.

More prevention: root drench

Potter also pointed out two other common landscape shrub problems caused by insect infestations that he says homeowners can treat by applying a root drench in March. If you have boxwoods or azaleas that don't look quite up to par, or that have discolored or oddly shaped leaves, root drench might help.

Among other problems, boxwoods are susceptible to two invasive insects: psyllids and leaf miners. Psyllids are teensy insects that are hard to see, but the signs that they've been active are easy to spot. In early spring, just as tender new boxwood leaves begin to grow, the boxwood psyllid nymphs hatch from eggs that were laid in the bud scales, and they feed on nearby leaves. They inject a toxin that causes an unusual cluster of cupped and bleached-looking leaves at the stem tips. The cupped leaves provide food and shelter for the psyllids as they grow.

Boxwood leaf miners, on the other hand, survive the winter as wiggling larvae after hatching from eggs sandwiched inside between the upper and lower leaf surfaces. As spring approaches, the larvae grow, then they break out of the leaves as little orange mosquito-like flies. Potter says the leaves take on the "appearance of pita bread blisters" where leaf miners are present. Leaf loss slows growth and creates an unhealthy-looking shrub.

Stressed azaleas in decline might be affected by azalea lace bugs, which suck chlorophyll out of the undersides of leaves, causing stippling and loss of color. To confirm your diagnosis, look for telltale black excrement spots on the backs of the leaves.

"I almost never see an azalea planting that does not have this problem, unless it's been treated," Potter says.

How to treat these problems? Potter, an expert on landscape insect pests, suggests using an application in mid- to late March.

"All of the aforementioned azalea and boxwood pests can easily be prevented by a one-time application of a homeowner-labeled systemic insecticide, for example Bayer Advanced Tree and Shrub Insect Control Concentrate, which provides season-long control," Potter said. "The product is mixed with water in a bucket and then mulch is raked away; the drench is applied to the base of the shrub and the mulch raked back in place.

"The key is to get it down some weeks before bud break, so that there is time for uptake to protect the new growth before critters, especially the boxwood psyllid, get it."

Although this involves the use of an insecticide, it does avoid general sÂpraying, which might affect beneficial insects, and it has been shown to be effective in controlling these pests, Potter says.

___

© 2009, Lexington Herald-Leader (Lexington, Ky.).

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

Novena for Pope Francis | FREE PDF Download

-

- Easter / Lent

- Ascension Day

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

St. Catherine of Siena: A Fearless Voice for Christ and the Church

Conclave to Open with Most International College of Cardinals in Church History

A Symbol of Faith, Not Fashion: Cross Necklaces Find Renewed Meaning Among Young Catholics and Public Leaders

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

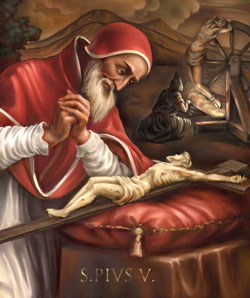

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025- Prayer for the Dead # 3: Prayer of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025