We ask you, urgently: don't scroll past this

Dear readers, Catholic Online was de-platformed by Shopify for our pro-life beliefs. They shut down our Catholic Online, Catholic Online School, Prayer Candles, and Catholic Online Learning Resources essential faith tools serving over 1.4 million students and millions of families worldwide. Our founders, now in their 70's, just gave their entire life savings to protect this mission. But fewer than 2% of readers donate. If everyone gave just $5, the cost of a coffee, we could rebuild stronger and keep Catholic education free for all. Stand with us in faith. Thank you.Help Now >

History, salt, sugar and prayer go into real country ham

FREE Catholic Classes

McClatchy Newspapers (MCT) - In the A.B. Vannoy Ham House, on a steep side street off U.S. 221 in Ashe County, N.C., the ham room is upstairs.

Highlights

McClatchy Newspapers (www.mctdirect.com)

12/15/2008 (1 decade ago)

Published in Home & Food

Hundreds of hams hang from wooden beams, each wrapped in brown paper and a loosely woven, white stocking.

To get there, you climb narrow wooden stairs as steep as a ship's ladder. Halfway up, you start to smell an aroma of meat, salt and wood that has been accumulating for more than 80 years.

When you reach the top, you have to move carefully. A ham starts out as 25 pounds of bone, fat and meat. It's a hard thing to bump with your head. From spring until fall, when the room is filled with the latest batch of curing hams, moving around is like trying to cross an attic strung with oversized baseball bats.

The only light comes from a dangling light bulb and deep windows on two sides. Through the windows, you can see the hill that stretches behind the ham house, covered with Christmas trees and thick meadow grasses.

Vannoy hams are all about those windows. These country hams are climate-cured, which means: Open windows. Windows that let in spring breezes and the humid heat of summer.

There aren't many places left that do it this way, letting the hams hang for at least eight months and especially through June, July and August, when heat activates the salt that has been driven into the ham through the cut end of the bone, driving out moisture to stop bacteria from growing.

Byron Jordan, who owns A.B. Vannoy, likes to say his hams have only four ingredients: "Salt, brown sugar, mountain air and time."

MARCH

In March, I headed back to the mountains, on a drizzly day when cows huddled in pastures tucked into the crooks of the hills. There aren't a lot of tourists here. These are the mountains of working people, where brick houses sit next to tumbling-down homeplaces with caved-in roofs.

North Carolina leads the nation in making country hams, according to Dana Hanson, an associate professor of food science at N.C. State University. Out of about 60 ham processors nationwide, 20 to 25 are here.

But most are climate-controlled houses that use heated rooms to hurry the process or to ensure consistency. The length of curing time, when hams develop deeper, more unique flavors, can vary from 75 days to 18 months or longer.

Open-air ham houses like Vannoy are rare. Hanson believes it may be the only one left in the state. He only knows of a couple of others, one in Kentucky and one in Missouri.

There used to be four ham houses in Ashe County, about 120 miles northwest of Charlotte, N.C. But the other three are gone now, closed by owners who no longer want to wrestle with state regulations and wait months for a product that few people want to buy.

Today, the only ham curers left are Jordan, 55, and his wife, Nancy. Owners of a small restaurant, Smoky Mountain Barbecue, they bought A.B. Vannoy Hams, started in the 1920s, when Vannoy's daughter got out of the business in 1994.

Each year, the Jordans buy more than 1,600 hams, most from pigs raised in the Midwest. They coat the hams in a mixture of salt and sugar for 36 days. They rinse them, wrap them in brown paper, slide them into loosely woven stockings, move them upstairs and hang them. There the hams wait, for at least seven months and as long as two years.

"Folks don't understand," says Jordan. "They'll say, 'Well, shucks _ I can get one at Ingles.'" But they don't know what goes into it, he says, or how long he has his money tied up in these hams. And sales are gradually declining, particularly for whole hams. "The people who know what to do with a whole ham are dying off."

But Jordan knows there's a different world out there, a world that is coming back around to slowly made foods crafted from special ingredients. In New York, ham aficionados pay up to $125 a pound for Spain's Iberico ham and as much as $12 a pound for prosciutto di Parma from Italy _ a long way from the $2.59 a pound Jordan gets for his ham.

He can't ship his hams to New York. His ham house is state inspected, so he can't sell across state lines. To get federally inspected, he's afraid he would have to change his operation, cover the old concrete walls and take out the wooden beams. That, he fears, might change his ham.

But this year, Jordan agreed to work with us on a project. In January, I brought the leg of an old-breed pig raised on Grateful Growers Farm in Denver, N.C., 35 miles north of Charlotte, to A.B. Vannoy. It was coated with Jordan's curing mix and left with the other hams while the salt and sugar worked their way into the meat.

Fifty-seven days later, fighting to see the road through thick fog, I returned to the ham house.

Once the hams are hanging, Nancy Jordan runs the business. She spends a lot of her time in the old ham house, where it's cold in winter and cool even in summer. She fills the ham orders, weighing, inspecting and wrapping the hams and shipping them to the customers.

When customers call, with praise or complaints, they talk to Nancy. She often looks worried, fretting about inspectors, about sales, about customers. What she really worries about is whether their business will survive.

She's from Plymouth, in Eastern North Carolina, and she grew up on country ham. But when Byron wanted to buy the business, she wasn't sure.

"I was raised on ham that was very, very salty. When we were approached about buying this business, I thought, 'I don't want that salty mess!' But then I tasted it. The sugar keeps it from being so salty. That's when I thought, 'I do like this ham. And I believe I can sell it.'"

She still likes it, but she only eats it at Thanksgiving and Christmas. "I don't want to get tired of it," she says. "Believe me _ I've had barbecue (from their restaurant) for 18 years. When you're trying to sell a product, you don't want to get tired of it."

I came in March to see my ham make its trip upstairs to the ham room. The other hams have already been moved, but mine was bigger, so it had to wait longer. The old-breed pig it came from grew faster than I expected, yielding a 37-pound ham.

It started out pink, then turned dark red and brown from the cure. Now the meat under the thick layer of fat looks kind of gray _ normal for a curing ham. When Byron rinsed off the curing mix, the fat looked startling white against the darkening meat.

Next, he wrapped the ham in brown paper, as they were taught when they bought the business. People in the mountains believe that brown paper stops larder beetles. Indigenous to the mountains, larder beetles bore into hams to lay their eggs.

In the old days, people didn't mind the eggs. They called them skippers, and they just cut them out and ate the rest of the ham. Meat was precious, and you didn't waste it.

Today, of course, it's different: "My customers would faint if they found a bug in their ham," says Nancy.

The only sure way to stop the larder beetle is to fumigate the ham house, which happens in May. It sounds strange, but it's required by law. Jordan has to close and tape up the windows and set off a canister of methyl bromide. It's odorless and colorless, and it kills bugs, but it doesn't affect meat. It's one of the only pesticides approved for use around food.

But the manufacture of it is now regulated. When the Jordans bought the business, it cost $150 for enough to treat the whole ham house. Now, it costs almost $1,000 and they have to do it twice.

AUGUST

In August, I returned for a visit. It was late summer, and the trees were festooned with gray clouds of tent caterpillars.

In the ham house, it was much quieter. "It's like a barn," said Nancy Jordan. "No heat, no air conditioning. We have to roll with the seasons."

Upstairs, a tall fan was roaring steadily, to keep the air moving and help the hams cure evenly. The trick to curing all these hams is consistency. You need heat to activate the salt, driving out moisture, but you don't want the meat to dry too quickly. If it's rainy, the hams can mold.

Of course, mold on a ham is part of the process. When you unwrap a country ham, it will be covered with it. Nancy dreads the calls from customers, upset because there's mold on the ham. She includes a label telling them to scrub the mold off, but she's had calls from people who told her they threw the ham away.

"Every Christmas, somebody calls with that. Oh, I just cry."

OCTOBER

On a chilly day in early October, nine months after it went to the mountains, it was time for the ham to come home to Charlotte. This time, I took along a guest, chef Joe Bonaparte of the Art Institute. Bonaparte has made several trips to Italy, where he has become enthralled with old-style meat curing, so he wanted to see a Southern curing house.

In the ham house, the chilling room downstairs had been turned into a meat-cutting room. Since so few people want a whole ham, Byron and Nancy Jordan have decided to branch out, cutting some of their ham into center-cut slices and vacuum-packing it for holiday gift packages.

Byron shows Bonaparte the oldest artifact of the business, handed down from the original owner: a stubby ice pick with a wooden handle. Before inspections and water analysis, this was how you checked hams. He still uses it, sliding the pick into the ham, pulling it out and sniffing it for the sour smell of spoilage.

In Italy, Bonaparte tells him, they use a horse bone, because it's porous and the smell clings to it.

"A horse bone?" Nancy Jordan gapes at him. "You are kidding me."

In the cutting room, they look at the hams that have been cut in half, pointing out the anatomy, the way the meat has darkened closest to where the salt goes in, the way crystallizing proteins have left little white spots.

A worker suddenly calls Jordan over. He's found a bad ham. Jordan leans in close, giving a whiff with his long nose, and nods solemnly.

"You treat two hams the identical same way. You salt them the same, you hang them side by side, and one will cure out and one won't."

Upstairs in the ham room, Bonaparte has to be careful _ he's tall, and the aged hams hanging from the beams are now as solid as bowling balls. The brown paper has tightened around them, almost as if they've been vacuum-packed.

He strolls around, looking at everything, and tells Jordan about ham houses in Parma, Italy, where hams cure in the breezes from the Mediterranean.

"What do they do for pest control?" Jordan asks him.

"I don't know," Bonaparte says, laughing. "I'm going over in two weeks. I'll try to find out."

What Jordan really wants to know: "What can we do to keep it going? To keep it profitable?"

He lifts our ham up off the nail where it has hung since March and carries it downstairs. Slitting open the netting, he peels back the brown paper, revealing patches of gray-green mold.

He slides the ice pick into the center and pulls it out, and we all lean in to smell. No sourness, just metal and the sweetness of meat.

Jordan moves the ham to a scale, then gets out a calculator. I hold my breath: It started at 37 pounds and now it's 29 pounds. It lost almost 22 percent of its weight _ just a little over the 18 percent minimum.

"Thank you, God," Nancy murmurs.

Bonaparte suddenly has an idea: They have the meat saw set up, why not cut into it? Jordan is willing, so he carries our ham to the saw, fires it up and then shaves off a few slices. Bonaparte picks up a sliver and eats it as the workers in the room _ even Nancy Jordan _ stare at him. He's eating raw ham?

Why not, Bonaparte reminds them. It's cured.

I take a piece, too. It's sweet and more delicate than I expect. The fat is creamy and clean-tasting.

NOVEMBER

The ham that started in a field in Denver, N.C., ended up on my back porch near Cotswold, N.C. The weekend before Thanksgiving, I invited a houseful of guests, including farmers Natalie Veres and Cassie Parsons, who raised the pig, chef Joe Bonaparte and one of his culinary students, Marla Thurman.

I had paid Veres $144 for the original ham, and $27.83 to the Jordans for the time it spent in their ham house. I had driven just over 1,000 miles to follow it through its yearlong journey.

I cooked the ham the traditional way, soaking it in water overnight and simmering it in a big pot all day. Then I cut away the skin, scored the fat and baked it until it was sizzling.

I made buttermilk biscuits, a grits souffle and collards. Then we all sat around the table, eating and admiring the ham. Under the table, I was wearing my black suede work shoes, with the gray imprint of a pig's snout still visible on one toe. So you could say the pig was there, too.

It wasn't prosciutto. It wasn't Iberico.

It was North Carolina country ham, a little salty, a little chewy, and a taste all our own.

___

WANT TO ORDER?

A.B. Vannoy Hams can't ship hams out of state. But you can order one within North Carolina.

Cost: Whole hams are $2.59 a pound; most are 13 to 18 pounds. They also have 12-ounce vacuum-packed packages of center and biscuit slices for $4.99 to $7.99. Gift boxes with several packages of slices and trimmings for seasoning are $26.

Orders: Call Smoky Mountain BBQ toll-free at 888-793-5371, or e-mail orders to smokymtnbbq@skybest.com. Hams also are sold at the restaurant, on U.S. 221 in West Jefferson, or at Thomas Bros. Meats, 347 Thomas St. in North Wilkesboro.

For more resources, try this N.C. Department of Agriculture site: www.ncagr.gov/markets/gginc/index.htm.

___

© 2008, The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, N.C.).

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

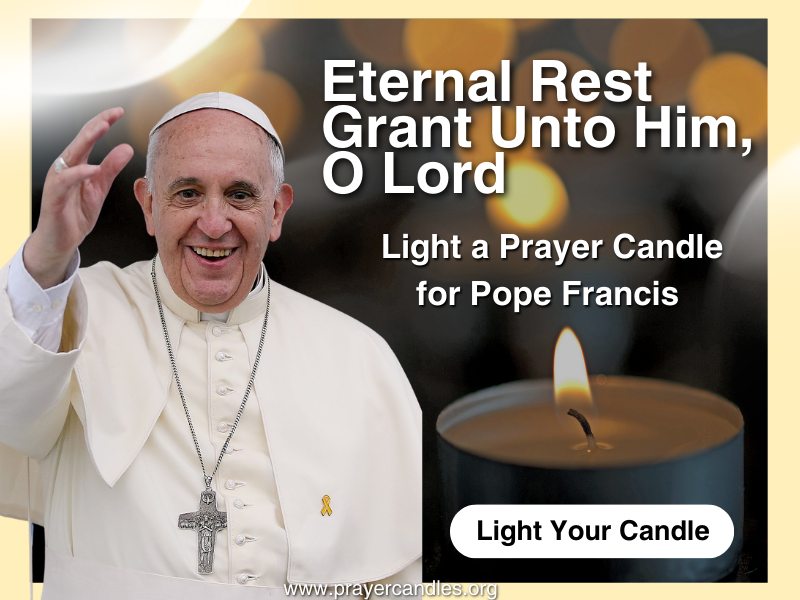

Novena for Pope Francis | FREE PDF Download

-

- Easter / Lent

- Ascension Day

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

St. Catherine of Siena: A Fearless Voice for Christ and the Church

Conclave to Open with Most International College of Cardinals in Church History

A Symbol of Faith, Not Fashion: Cross Necklaces Find Renewed Meaning Among Young Catholics and Public Leaders

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

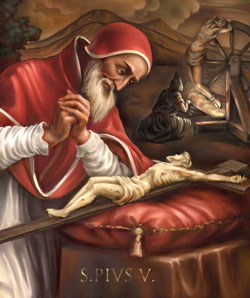

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025- Prayer for the Dead # 3: Prayer of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025