Dear readers, Catholic Online was de-platformed by Shopify for our pro-life beliefs. They shut down our Catholic Online, Catholic Online School, Prayer Candles, and Catholic Online Learning Resources essential faith tools serving over 1.4 million students and millions of families worldwide. Our founders, now in their 70's, just gave their entire life savings to protect this mission. But fewer than 2% of readers donate. If everyone gave just $5, the cost of a coffee, we could rebuild stronger and keep Catholic education free for all. Stand with us in faith. Thank you. Help Now >

Dear readers, Catholic Online was de-platformed by Shopify for our pro-life beliefs. They shut down our Catholic Online, Catholic Online School, Prayer Candles, and Catholic Online Learning Resources essential faith tools serving over 1.4 million students and millions of families worldwide. Our founders, now in their 70's, just gave their entire life savings to protect this mission. But fewer than 2% of readers donate. If everyone gave just $5, the cost of a coffee, we could rebuild stronger and keep Catholic education free for all. Stand with us in faith. Thank you. Help Now >

Far East promise: China's potential lures adventurous winemakers

FREE Catholic Classes

Chicago Tribune (MCT) - Fred Nauleau, late of the Loire Valley, blinked up at the relentless sun above his adopted home beside the snowcapped Tian Shan mountains.

Highlights

McClatchy Newspapers (www.mctdirect.com)

10/20/2008 (1 decade ago)

Published in Home & Food

He stood amid giant new warehouses and processing facilities _ the boxy, workaday headquarters of a winemaking empire that he has helped build in less than a decade from this redoubt in the western reaches of China. It's an ambitious project in a nation where most people still call the unfamiliar beverage "red liquor."

"In 2000, most of these buildings weren't here," said Nauleau, a phlegmatic and compact 42-year-old, with bright blue eyes and a shock of unruly brown curls. "In the beginning, it was quite difficult."

The fertile plains of Xinjiang Province _ closer in culture and geography to Istanbul than Beijing _ have lured speculators since the days of the Silk Road. Nauleau is part of a new generation of adventurers who are gambling that this land can produce wine that is good enough to traverse the globe.

They are betting on geography: Xinjiang, which is more than three times the size of France, sprawls across the 45th parallel, the mythic ribbon of the planet that slices across Bordeaux, Piedmont and Oregon. In Xinjiang, the temperate climate along the 45th produces vast fields of sunflowers and cotton, as well as table grapes and melons that are renowned for their sweetness. Xinjiang produces enough tomatoes not only to feed China but also to send to Italy, where they are canned and relabeled to give them a more familiar provenance.

Nauleau is the winemaker for Vini-Suntime International, which calls itself the largest wine producer in Asia. It has 25,000 acres of vineyards in China, six wineries, and a total bottling capacity of 200 tons of wine per day. Some of that wine is sold in America under the label, China Silk, which was launched in 2006. It is sold in 14 states and expected to be available nationwide by the end of 2009, according to its president, Steve Clarke.

Most of Suntime's product is consumed in China, which has begun to look beyond its traditional favorites, beer and the ferocious grain alcohol known as baijiu, to consume a growing share of wine, including some of the world's best. In a sign of growing interest among Chinese collectors, Hong Kong earlier this year scrapped its tax on wine, and later, held a record-breaking wine auction. In January, a Chinese company bought a Bordelais chateau called Latour-Laguens, the first acquisition of its kind by a Chinese firm.

A California-based company has even begun offering wine tours. No visitor has generated as much attention as the critic Robert Parker, who made his inaugural visit to China this year.

In May, British wine merchant Berry Bros. & Rudd released a report predicting that, in 50 years, China will be the world's leading supplier of wine, including cabernet sauvignon and chardonnay to rival French offerings.

Some question the scale of that prediction, though China's 1.3 billion consumers, with a proud culinary culture, make it an important new player. China's 400 producers already rank the nation as the world's sixth largest producer, ahead of Chile and South Africa. Outside China, however, there is little knowledge of the country's brands, which include Dragon's Hollow, Grace Vineyard, Great Wall, Chateau Junding, Catai and China Silk.

The greatest challenge for Chinese producers, however, is not quantity.

"The joke about Chinese wine was always, 'Have you tried Chinese wine _ leaded or unleaded?'" said Jim Boyce, a Canadian who lives in Beijing and runs Grapewallofchina.com, a well-read blog covering the nation's growing market and production.

Indeed, much of China's wines are unsatisfying to Western palates. "Very, very thin, not quite clean, red Bordeaux," critic Jancis Robinson wrote of what she tasted on early visits in 2002 and 2003. Since then, Chinese wines have been slow to improve because high-end buyers look abroad, while the rest of the market has so little experience with wine that it is content to buy the cruder offerings.

"So the incentive for improving the wine is quite light," Boyce said. "But I think improvement is coming. The Chinese people pick up trends very quickly and they get sophisticated about new things very quickly. You are already seeing that in the number of wine bars opening up."

China has a deeper history with wine. In 2004, scientist Patrick McGovern, of the University of Pennsylvania, uncovered what he called the world's earliest evidence of deliberate winemaking, from a Neolithic village named Jiahu, in north-central China's Henan province. That find, which dated from between 6,000 B.C. and 7,000 B.C., replaced what McGovern had previously considered the oldest evidence of winemaking, from around 5,400 B.C. in what is now northwestern Iran.

Wine fell out of favor in modern China, but Xinjiang continued to produce a wide variety of grapes for table fruit and raisins. Modern winemaking only began in the late 1970s after Deng Xiaoping launched China down the path of reform.

The new industry attracted some surprising entrants. Neuleau's employer, Vini-Suntime International Co., Ltd., began in 1998 with the backing of a conglomerate that owns everything from coal fields to hotels to petrol plants. From the beginning, it had a global outlook: It imported technology from France, Italy, the United States, Germany and Switzerland, and exported bulk wine to the United States, France, Cuba and other countries. Desks in the sales department are piled with books such as "Speaking Russian" and "Speaking Japanese."

When Nauleau arrived in 2000, after a career in vineyards and wine labs in France, he had been lured by the prospect of travel. He was no stranger to developing countries. He had previously helped get wineries off the ground in Bulgaria. But, even so, he was taken aback by what he found in China.

"The workers were very young. They had more experience in the baijiu industry or fermentation but not in wine," he said. "I had to show them how to connect a pump. I installed my desk in the cellar and had a big white board and said, 'OK, you have to connect the A8 to B10 and so on.'

"I stayed here because I was so surprised with the quality of the grapes," he added.

He learned Chinese, met and married a woman from the area and, except for three years back in France, he has remained ever since in Manas, a low-slung town about an hour's drive from Urumqi, the provincial capital.

This is not quite Bordeaux. Though Xinjiang sits on the same 45th parallel, it sits farther from the sea than almost any place on the planet. That makes the climate drier and prone to more dramatic swings than other wine-growing regions. By contrast, many of China's wine producers are based in Shandong on the eastern coast. But even there they are beset by vine diseases in the damp and humid climate. Nauleau and other Xinjiang winemakers have come to see their location as an ideal place to develop Chinese wine.

"We have less than 200 millimeters of rain a year. That means we rely on irrigation, and the water comes mostly from the Tian Shan mountains. So we can control the amount of water," he said. "The grapes are sweeter because of the difference in temperature between the day and night. And there is more than 1,600 hours of sunlight per year. Because the climate is dry, there are very few pests, so no need for pesticides."

Suntime's vineyards stretch to the horizon. Only the faint Chinese characters stenciled on the road signs mark this as China. Though winery worker Ding Fanhua, 24, knew little of wine before he landed this job, he now helps oversee a crop made up of the same varieties found in Bordeaux: cabernet sauvignon, merlot, syrah and cabernet franc.

"There was a lot of snow last year, so the grape output this year will be down," Ding said, crouching to examine some small plump fruit. "This year the weather is hot and there is little rain so the grape color will be good and the sugar level will be good."

As in other new winemaking regions along the 45th parallel, Nauleau is familiar with predictions that global warming could usher in a new ascendancy. He doesn't know if they will hold true, but he has already seen how temperature changes can affect his wines.

"In 2000, the snow was falling even while we are still picking the grapes," he said. "I'll never forget that. But last year, for example, even at the end of November it was not too cold.

"Here the sugar matures first. Then the tannins mature," he said, adding that if global warming raises the temperature in his region, "it could narrow that gap. We can get some more ripe tannins and color. So more like Chilean wines."

A glimpse of the future of Chinese wine can be seen in Nauleau's prized cellar, where he has cabernet sauvignon and merlot aging for at least one year in barrels made of French oak and American oak. Some of that wine ends up in France, mostly in Chinese restaurants. When he returns to France for visits, he is proud to offer fellow winemakers some of his creations.

"I buy them a bottle and they are quite surprised," he said. "They don't know _ nobody knows _ about Chinese wine. That it can be good, I mean."

___

BY THE NUMBERS

1.2 million _ Approximate number of vineyard acres in China

8 _ Major wine regions in China

___

© 2008, Chicago Tribune.

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

Novena for Pope Francis | FREE PDF Download

-

- Easter / Lent

- Ascension Day

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

St. Catherine of Siena: A Fearless Voice for Christ and the Church

Conclave to Open with Most International College of Cardinals in Church History

A Symbol of Faith, Not Fashion: Cross Necklaces Find Renewed Meaning Among Young Catholics and Public Leaders

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Thursday, May 01, 2025

Daily Readings for Thursday, May 01, 2025 St. Marculf: Saint of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025

St. Marculf: Saint of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025 To Saint Peregrine: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025

To Saint Peregrine: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025 Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

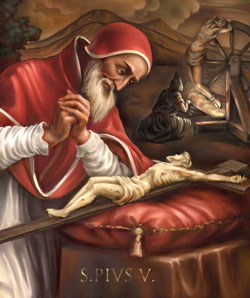

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025- Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Thursday, May 01, 2025

Daily Readings for Thursday, May 01, 2025 St. Marculf: Saint of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025

St. Marculf: Saint of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025 To Saint Peregrine: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025

To Saint Peregrine: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025