Recapturing the Two Wings of Faith and Reason

FREE Catholic Classes

Perhaps the two wings of reason and faith that inform the Catechism may, with a bit of grace and with some sincere prayer, find their way into your mind and heart and therein engender love, love of the God-man Jesus, the Logos (Reason) made Flesh (John 1:14), in whom "we see our God made visible and so are caught up in love of the God we cannot see."

Highlights

Catholic Online (https://www.catholic.org)

8/21/2013 (1 decade ago)

Published in Living Faith

Keywords: faith, reason, Lumen Fidei, Fides et Ratio, secularism, empiricism, Andrew M. Greenwell

CORPUS CHRISTI, TX (Catholic Online) - "The Church is a house with a hundred gates," wrote G. K. Chesterton in The Catholic Church and Conversion, "and no two men enter at exactly the same angle." Whatever angle is taken by any one man or any one woman, there are two things that must accompany any pilgrim: faith and reason.

Anyone who thinks he can reach Christ without the use of his reason is on a fool's quest. He won't become a Christian. Rather, he will become a Fideist, or worse, will fall into superstition.

Anyone who thinks he can reach Christ without faith is horribly misguided. He will not become a Christian. Rather, he will become a Pelagian, or worse, a Rationalist, or even worse, a Skeptic.

When Blessed John Paul II wrote his encyclical on faith and reason Fides et Ratio in 1998, he did not entitle it Fides aut Ratio--Faith or Reason, but Fides et Ratio, Faith and Reason.

"Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of the truth," he famously wrote.

Ultimately, it is the burden of that encyclical to show that faith and reason lead to the same answer: Jesus Christ and His Church, the Catholic Church.

As Chesterton again wrote, this time in his essay "Why I am a Catholic," his difficulty with explaining to others as to why he had become Catholic was "that there are ten thousand reasons all amounting to one reason: that Catholicism is true."

Just as reason will lead to the conclusion that there must be one God, it will lead inescapably to the conclusion that the only true faith is the Catholic Faith. St. Paul said that faith will lead one to recognize that there is "one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all." (Eph. 4:5-6).

Unfortunately, reason can be dreadfully slow in coming to its conclusions. That's why G. K. Chesterton observed that reason might need to be jump started, as it were, by faith. Yet G. K. Chesterton was insistent that right reason would lead one invariably--given enough time--to the Catholic creed: "If every human being lived a thousand years, every human being would end up . . . in the Catholic creed," he wrote in his essay on William Blake.

The other possibility was, of course, that someone would use wrong reason for a thousand years, in which case he would end "in utter pessimistic skepticism."

In the area of faith and reason, there are some basic questions no inquiring mind can ignore.

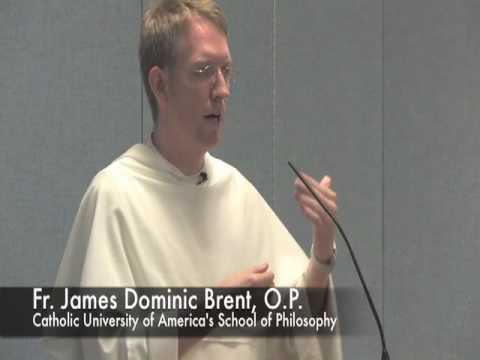

In his Critique of Pure Reason, the Enlightenment philosopher Kant famously identified three such questions, which, ultimately in his Logic he distilled into one.

Was kann ich wissen? Was darf ich hoffen? Was sol ich thun?

What can I know? What dare I hope? What shall I do?

These three he distilled into: Was ist der Mensch? What is man?

Now poor Kant made a categorical mistake by supposing the answers to these questions could be attained by pure reason, and pure reason alone. Like a bird with one wing--even if that wing is huge--Kant fluttered about impressively, but never got off the ground and certainly never approached anything like the God of Jesus Christ or his Church. In fact, his efforts seem to have landed him into some serious skepticism thinking he could never know even the world, much less God. He was condemned only to know what he thought about the world.

An honest person will come to the same conclusion that Pope Francis did in his recent encyclical, Lumen Fidei: "Slowly but surely . . . it would become evident that the light of autonomous [i.e., pure] reason is not enough to illumine the future. . . . As a result, humanity renounced the search for a great light, Truth itself."

In his encyclical Faith and Reason, Blessed John Paul II put the Kantian questions in a different form, perhaps a form more in keeping with his phenomenological and personalist bent. He called them the fundamental questions, and he identified five of them:

Quis egomet sum? Who am I?

Unde venio? Where have I come from?

Quoque vado? And where am I going?

Cur mala adsunt? Why is there evil?

Quid nos manet hanc post vitam? What is there after this life?

These five fundamental questions branch out into ten thousand difficulties. But as Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman observed, "Ten thousand difficulties do not make one doubt." Questions and difficulties are the grist of reason and the stuff of faith.

So, in answering these fundamental questions and their difficulties, how do we come about right reason and avoid the reason that leads to skepticism?

First, we have to reject the modern belief (and it is a belief, entirely based upon faith or unstated assumptions), that reason is limited to the things we see: empiricism or scientism. In his book A Fractured Relationship, Father Thomas J. Norris describes this event as the loss of "strong reason," and the adoption of "weak reason." We have to re-acquire "strong reason."

Other ways of phrasing this arbitrary restriction on reason which leads to its blindness to greater Truth are as follows. The poet William Blake called it a "single vision," a sort of myopia that gave rise to "Newton's sleep." We have to rouse ourselves from Newton's sleep and gain binocular vision, as it were.

While recognizing the importance of "weak reason" called ratio, the medieval philosopher recognized a "strong reason," one more contemplative and disposed to answering the fundamental questions, which he would have called intellectus or simplex intuitus. We need to regain contemplation.

The sociologist Max Weber referred to this limitation of reason as something akin to putting our reason into a stahlhartes Gehäuse, an "iron cage" or "hardened steel-like shell." We need to take our reason out of the cage (or Plato's cave) and let it ponder on the greater reality out there.

The historian of modern secularism Charles Taylor has called this the adoption of an "immanent frame" of reference, one that by arbitrary faith excludes the possibility of a "transcendent frame." We have therefore to get out of the restrictive frame of reference, and adopt a broader one.

Whatever one may call this burden under which we labor and from which we must emancipate ourselves, it is in each and every instance a restriction, a limitation, a lack of confidence in reason that we have to reject.

We have to experience a conversion of reason from the dark anti-faith of the Enlightenment which has caged it, tamed it, emasculated it, weakened it.

The Canadian theologian Bernard Lonergan studied the problem of the "immanent frame," the "iron cage" of secularity, "Newton's sleep," or "weak reason." He proposed that we adopt "transcendental precepts" in our reason as the means out of this modern intellectual trap. He identified four precepts:

Be attentive.

Be intelligent.

Be reasonable.

Be responsible.

Ultimately, by striving to be attentive, by being intelligent about what our senses tell us about the world, by behaving reasonably toward reality, and by being responsible intellectually and morally, Lonergan believed that, with the help of a little actual grace, we might be lead to a three-fold conversion over time: an intellectual conversion, followed by a moral conversion, which ultimately would lead to a religious conversion.

But for most of us, this may be too long a process. We don't all have a thousand years and we don't all have leisure, so if we have not yet accepted Christ and His Church as the only true answers to the questions Who am I? Where have I come from? Where am I going? Why is there evil? And what is there after this life? Then we had better get started or find a short cut.

To be sure, the problem has already been thought out by minds greater than most of ours, and by a teaching authority founded by Christ. Rather than starting from scratch, you could pick up the Catechism of the Catholic Church, for therein you will find faith and reason, wonderfully combined, wonderfully synthesized.

And who knows? Perhaps the two wings of reason and faith that inform the Catechism may, with a bit of grace and with some sincere prayer, find their way into your mind and heart and therein engender a flutter of love, love of the God-man Jesus, the Logos (Reason) made Flesh (John 1:14), in whom "we see our God made visible and so are caught up in love of the God we cannot see." (Christmas Preface I)

It happens. I knew an erstwhile Baptist woman who, at age 12, happened upon a Baltimore Catechism and before she closed the book, she knew it to be God's truth, and against the chagrin of her parents, walked to the closest Catholic Church and asked the priest to be let in. And she was Catholic ever since.

-----

Andrew M. Greenwell is an attorney licensed to practice law in Texas, practicing in Corpus Christi, Texas. He is married with three children. He maintains a blog entirely devoted to the natural law called Lex Christianorum. You can contact Andrew at agreenwell@harris-greenwell.com.

---

'Help Give every Student and Teacher FREE resources for a world-class Moral Catholic Education'

Copyright 2021 - Distributed by Catholic Online

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

An Urgent Message from Sister Sara – Please Watch

- Advent / Christmas

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.