Fertilizer prices soar, but makers cite oversupply

FREE Catholic Classes

Star Tribune (Minneapolis) (MCT) - Jim Nichols braced himself for a big number when he recently called his local grain elevator for a price on phosphate, a key ingredient of fertilizer.

Highlights

McClatchy Newspapers (www.mctdirect.com)

10/9/2008 (1 decade ago)

Published in Business & Economics

Even so, the Lake Benton, Minn., corn farmer and former state agriculture commissioner found himself laughing _ nervously _ after the fertilizer dealer told him the price: $1,025 per metric ton, up from just $520 a year ago. "It was humorous until I learned that he wasn't kidding," Nichols said. "Then I started to worry."

Indeed, in the eyes of many farmers and agricultural experts, fertilizer prices have seemed to defy the normal laws of economics. Despite the high prices, makers of phosphate and potash _ another key fertilizer ingredient _ say there's an oversupply and earlier this month, Plymouth, Minn.-based Mosaic Co. said that it would scale back production, the second major company in recent weeks to announce production cuts.

Mosaic, the world's largest producer of phosphate and potash, said it will cut phosphate production by 500,000 to 1 million metric tons over the next several months. That's about 10 percent of the company's annual production. Potash Corp. of Saskatchewan, another large fertilizer company, in September idled about 30 percent of its production capacity because of a labor strike.

Both companies are dealing with their own financial issues, including share prices that have plummeted 50 percent or more since their peaks in mid-June. Mosaic, which is majority owned by agricultural giant Cargill Inc., closed Wednesday at $35.75. The stock traded at more than $160 in June.

As a result of curbed production, it's not likely that fertilizer prices will decline anytime soon, agricultural analysts say. Mosaic, in fact, said that it expects the average price of phosphate to be around $1,020 to $1,080 a metric ton (about 2,200 pounds) _ virtually unchanged from its current level _ through the second quarter. Many farmers buy their fertilizer in the fall and seed in the spring, which means they won't be able to avoid the current high prices.

Farmers were told this year that rising fertilizer prices were the result of increased demand for grains, leaving some hopeful that fertilizer prices would fall once commodity prices dropped. But the agricultural commodities bubble has burst in recent weeks _ corn closed Thursday down 43 percent from June highs and soybeans fell to an 11-month low _ amid an unfolding global economic slowdown; yet fertilizer prices have continued to surge upward.

Some farmers have turned their anger toward local grain elevator operators, while others have begun to suspect the fertilizer companies of manipulating prices, said Bob Zelanka, executive director of the Minnesota Grain and Feed Association. "It certainly does have the feel like they're controlling the supply to drive up price," he said.

In a federal lawsuit filed last month in Minneapolis, Mosaic and seven other large fertilizer companies were accused of conspiring since 2004 to limit competition and drive up prices of potash, which have more than tripled over the past year. Mosaic has denied the allegations.

James Prokopanko, chief executive officer of Mosaic, said his company's decision to cut production was a reaction to an excess inventory buildup _ and was not designed to keep prices high. In the commodity price boom that occurred in the spring and summer, fertilizer distributors stockpiled huge amounts of phosphate, before prices rose even more. Many warehouses that store fertilizer nutrients are now almost full, and would have no place to store any increase in production, Prokopanko said. Once farmers work through these excess supplies, Mosaic will increase production again.

An unusually wet spring across much of the nation added to the excess supply. Prokopanko said many farmers planted their crops later than usual, and the late harvest has caused them to postpone fertilizer purchases _ adding to the stockpiles.

"The whole system is backed up," Prokopanko said. "We have no place to put this product we're manufacturing."

Jason Walsh, agronomy manager with Glacial Plains Cooperative, a farmers cooperative in Murdock, Minn., that sells fertilizer, said he wasn't aware of "excess supplies" in the fertilizer market and was surprised that Mosaic would make such an assertion. He said fertilizer buying patterns remain the same now as past years, and he hasn't seen any evidence of stockpiling.

"Something else is happening," Walsh said. "The phosphate market is getting soft, so they're cutting back production to maintain $1,000 (a metric ton) prices. It's by design."

(EDITORS: STORY CAN END HERE)

Mosaic is not the only agricultural company facing challenges. Excess supplies, sinking commodities prices and fears of a widening credit crisis have sent shares of farm-related companies into a tailspin in recent weeks. Shares of Monsanto have fallen from more than $140 a share in June to $81.44 on Wednesday, a decline of about 40 percent. Grain processors Archer Daniels Midland Co. and Bunge Ltd. have experienced similar declines.

David Swenson, an associate scientist in the Economics Department at Iowa State University, likened the run-up in agricultural stocks in the spring to the technology bubble of 2000 and 2001, when investors suddenly realized that demand would not grow indefinitely.

"You had this incredible supposition that every kind of commodity would go up in price," he said.

"All of a sudden, that view changes a little bit, and ripples all the way through the agricultural production system."

___

© 2008, Star Tribune (Minneapolis)

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

Novena for Pope Francis | FREE PDF Download

-

- Easter / Lent

- Ascension Day

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

St. Catherine of Siena: A Fearless Voice for Christ and the Church

Conclave to Open with Most International College of Cardinals in Church History

A Symbol of Faith, Not Fashion: Cross Necklaces Find Renewed Meaning Among Young Catholics and Public Leaders

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Thursday, May 01, 2025

Daily Readings for Thursday, May 01, 2025 St. Marculf: Saint of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025

St. Marculf: Saint of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025 To Saint Peregrine: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025

To Saint Peregrine: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025 Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

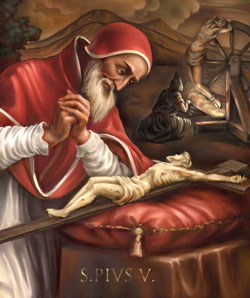

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025- Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Thursday, May 01, 2025

Daily Readings for Thursday, May 01, 2025 St. Marculf: Saint of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025

St. Marculf: Saint of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025 To Saint Peregrine: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025

To Saint Peregrine: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, May 01, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025