Dear readers, Catholic Online was de-platformed by Shopify for our pro-life beliefs. They shut down our Catholic Online, Catholic Online School, Prayer Candles, and Catholic Online Learning Resources essential faith tools serving over 1.4 million students and millions of families worldwide. Our founders, now in their 70's, just gave their entire life savings to protect this mission. But fewer than 2% of readers donate. If everyone gave just $5, the cost of a coffee, we could rebuild stronger and keep Catholic education free for all. Stand with us in faith. Thank you. Help Now >

Dear readers, Catholic Online was de-platformed by Shopify for our pro-life beliefs. They shut down our Catholic Online, Catholic Online School, Prayer Candles, and Catholic Online Learning Resources essential faith tools serving over 1.4 million students and millions of families worldwide. Our founders, now in their 70's, just gave their entire life savings to protect this mission. But fewer than 2% of readers donate. If everyone gave just $5, the cost of a coffee, we could rebuild stronger and keep Catholic education free for all. Stand with us in faith. Thank you. Help Now >

Converging and Convincing Proof of God: Beauty Ever Ancient Ever New

FREE Catholic Classes

"Everyone loves the beautiful," wrote St. Thomas Aquinas in his expositions on the Psalms. Because the experience of the beautiful is something well-nigh universal, it seems fitting to look at our experience of beauty, the pleasing aesthetic experience, as a possible source for a converging and convincing proof that God exists.

Highlights

Catholic Online (https://www.catholic.org)

12/24/2012 (1 decade ago)

Published in Year of Faith

Keywords: proof of God, beauty, illative sense, art, moral good, saints, Andrew M. Greenwell

CORPUS CHRISI, TX (Catholic online) - "Every human person loves the beautiful," unde omnis homo amat pulchrum, wrote St. Thomas Aquinas in his expositions on the Psalms. Because the experience of the beautiful is something universal, it seems fitting to look at our experience of beauty, that pleasing aesthetic experience, as a possible source of a converging and convincing proof that God exists. We shall see that only God, as Beauty Himself, seems capable of explaining the beautiful in nature, in human art and moral action, and in the human experiencing of beauty.

In his audience of July 10, 1985, Blessed John Paul II briefly discussed the "proof" of God through beauty, a quality of this world and things of it "which impels us to raise our gaze aloft," to find a transcendent Source for beauty. Seizing as his point of departure Psalm 19, where the Psalmist declares that the heavens proclaim the glory of God, the Pope introduces the subject only to treat it very quickly. But we might use his short reflections as a basis for further elaboration.

Beauty, Blessed John Paul II stated, is found in three places: in nature, in human art, and in the morally noble and self-less acts of man, in particular, the saints.

Beauty "is manifested in the various marvels of nature," begins Pope John Paul II. And who can disagree?

What shall we say about the experience of nature's beauty in a pacific sunset in Hawai'i gently framed by bowing palms with their fronds billowing in the soft, salty wind? Or a winter's landscape in a still New England January evening awash in the light of a full moon? Or in the inhibiting snow-capped Himalaya caped seductively in the soft yellow-orange of the alpenglow? Or at the sound of wind rushing through millions of shimmering leaves in groves of mountain aspen in a Colorado summer? Or at the enchantment which strikes us at the remarkable repertoire of the throstling sound of the Song Thrush? Are these fleeting moments of beauty not a sign of One "whose beauty is past change" and who "fathers-forth" such natural beauty?

This insight is at the heart of Gerard Manley Hopkins's poem "Pied Beauty":

Glory be to God for dappled things-

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches' wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced-fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change: Praise Him.

Beauty, Blessed John Paul II continued, is also "expressed in the numberless works of art, literature, music, painting, and the plastic arts."

In a notable passage, Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI) wrote about the "encounter with the beautiful" in art. He recounts his experience with the Lutheran Bishop Hanselmann at a Bach concert conducted by Leonard Bernstein after the death of the conductor Karl Richter. "When the last note of one of the great Thomas-Kantor-Cantatas triumphantly faded away," he wrote, Bishop Hanselmann and then-Archbishop Ratzinger looked at each other spontaneously said the same thing; "Anyone who has heard this, knows that the faith is true."

Ratzinger also expressed a similar experience when confronted with the beauty of Rublëv's famous Icon of the Trinity. For Ratzinger, the encounter with beauty is an encounter with truth, which means in some way an encounter with God, the source of both. "Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know," wrote Yeats in his famous poem on the Grecian urn, pointing to the incomprehensible and supra-rational in beauty and its tie into truth. Surely all of us have experienced such a thing?

Finally, though often forgotten in an age of utilitarian ethics, beauty Pope John Paul II observed is "appreciated also in moral conduct: there are so many good sentiments, so many stupendous deeds."

What else other than sheer beauty, sheer nobility is there in Blessed Teresa of Calcutta's devotion to the dead and the dying, to the world's poor and sick. Did she not describe it as doing "something beautiful for God"?

What else other than beautiful can we call St. Maximilian Kolbe's selfless act in giving up his life for the husband and father Franciszek Gajowniczek at Auschwitz, one of the world's most ugly places? What moral beauty may be found in the heroic, if simple words: "Ich bin katholischer Priester, ich möchte für den da sterben, Ich bin alt und allein, und er hat Frau und Kinder." I am a Catholic priest, I wish to die in his place. I am old and alone, and he has wife and children."

Blessed Mother Teresa of Calcutta and St. Maximilian Kolbe acted out a moral poetry which is nothing less the beautiful. The more we approach sinlessness, the more beautiful we are. That is why the Saints' lives are beautiful. We might remember that the Blessed Virgin Mary, who was conceived without sin, is traditionally regarded as the most beautiful of all creatures: Tota pulchra es, Maria, et macula originalis non est in te. "You are all beautiful, Mary, for there is no original stain of sin in you."

Beauty is felt as something received, not only the beauty in nature, but even the beauty that arises when the artist or the saint "cooperates by his action in its manifestation." Beauty, says the holy Pope, is discovered and admired fully only when man "recognizes its source, the transcendent beauty of God." In a word, beauty is grace, and all grace is from God.

Though often overlooked because it is not found in his well-known Summae, St. Thomas Aquinas advanced a proof of God's existence from beauty. We can find it expressed by the young St. Thomas Aquinas in his Commentary on the Sentences.

"In everything in which is found a more and less beautiful (speciosum), there is found some principle of the beauty (speciositatis principium), and something is called beautiful by its nearness to it."

This beauty is found in things that are sensed (a beautiful woman, a beautiful painting, a beautiful act of self-sacrifice). But there is also intellectual or spiritual beauty. Mathematicians, for example, have spoken about the beauty of their discipline. Bertrand Russell famously wrote in an essay, "Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty--a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture, without appeal to any part of our weaker nature, without the gorgeous trappings of painting or music, yet sublimely pure, and capable of a stern perfection such as only the greatest art can show." If mathematics is beautiful, a human soul infused with sanctifying grace and the angels of God, we may believe, are even more beautiful.

St. Thomas recognized both sensual and intellectual forms of beauty, insisted that the intellectual form of beauty was superior, but also insisted that they both participate in the same reality, the transcendent Beauty.

"Now we see a body to be beautiful in a sensible way (specie); a spirit more beautiful in an intelligible way (specie)."

What is this beauty that spans both the senses and the intellect? Surely it is a transcendent reality? And precisely such does St. Thomas conclude: "Therefore it is necessary that there be something by which both are beautiful, to which created spirits more draw near to." This something is God, the preeminent Beauty.

Created spirits such as man "draw near to" beauty, says St. Thomas. Subjectively, we are capable of experiencing beauty. Man is capax pulchri, capable of relating to beauty, like he is capax Dei, capable of relating to God.

A materialist philosophy has an almost impossible time explaining the human capacity for, the human experience of, and the human delight in, beauty, as much as it has difficulty in explaining man's constant hankering after God. As Arthur J. Balfour stated in his 1914 Gifford Lectures in an understated British way, there is a certain "incongruity between our feelings of beauty and a materialistic account of their origin."

To argue that our sense of beauty--something which seems to contribute little to theory of natural selection which materialist evolutionists tout as the full and entire explanation for man's existence--is a product of chance, "harmonizes ill with the importance which civilized man assigns" to beauty in the "scheme of his values."

No, it seems more sensible to believe, like the philosopher F. R. Tennant put it, that "the beauty of Nature may not only be assigned a cause, but also a meaning, or a revelational function." In other words, nature's beauty, and by extension the beauty in human art and human moral action, speaks to us about the Creator God.

A one-dimensional, materialistic, empirically-based scientific knowledge can tell us nothing virtually nothing about beauty. As the physicist John Polkinghorne put it at the beginning of his book The Way the World Is: "Beauty slips through the scientist's net." Have science explain the beauty of the Grand Canyon, or the beauty of a Giotto fresco, or the beauty of chastity and St. Francis rolling in the snow, St. Bernard throwing himself in an icy pond, and St. Benedict diving into a thorny bush to preserve the virtue. It can't.

Unfortunately, the bluntness, we might even say the philistinism, of science and technology and consumerist capitalism means that there is often no appreciation of beauty in our hyper-technical, economically-efficient, and consumer-oriented world.

The Swiss Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar believed there was a real need among moderns to rediscover the beautiful because encounter with the beautiful led to the encounter with God. As he wrote in his book Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics: "Our situation today shows that beauty demands for itself at least as much courage and decision as do truth and goodness, and she will not allow herself to be separated and banned from her two sisters without taking them along with herself in an act of mysterious vengeance."

So we must leave science whose sensitivities are dulled to the reality of beauty, and adopt the more flexible and more broad way of thinking that John Henry Newman called the illative sense. Using this illative sense, can we not say, must we not say, that there must be some underlying ground to the beauty of things, a Beauty behind all things beautiful? A Beauty to which we appear to have a intrinsic disposition, a sort of naturally-built inclination? Are we not indirectly encountering God when we encounter beauty whether in nature, in art, or in moral selflessness?

Emily Dickinson wrote about the elusive, and yet real, quality of beauty, beauty that is not caused by man and so must be caused by an Other, beauty that may be chased without ever being caught, and beauty which abides even if it is not chased.

Beauty -- be not caused -- It Is --

Chase it, and it ceases --

Chase it not, and it abides --

It remains something that we chase, but which, as it is a transcendent reality, is something we cannot ever hope to comprehend, whether it is the beauty behind a beautiful woman, a simple mathematical formula, the aurora borealis in north Alaska, Michelangelo's Pieta at St. Peter's in the Vatican, or the marvelous church of Mont Saint Michel in Normandy. It remains as elusive as catching the wind, for it is something of the spirit, and like the Spirit, it blows where it will. (cf. John 3:8)

Overtake the Creases

In the Meadow -- when the Wind

Runs his fingers thro' it --

Deity will see to it

That You never do it --

Beauty, though certainly intelligible, remains undefinable as God is undefinable. That, however, does not make it less real.

The Definition of Beauty is

That Definition is none --

Of Heaven, easing Analysis,

Since Heaven and He are one.

So wrote Emily Dickinson. She was in an Augustinian mood that day. Si comprehenderis, non est Deus. If you understand it, it is not God, St. Augustine said, emphasizing the incomprehensible Truth that is God. He may have just as well said, si comprehenderis not est Pulchrus. If you understand it, it is not Beauty, at least not the Beauty ever Ancient ever New.

For Augustine knew that whereas there is beauty in created things that we experience, there is only One in Whom beauty is not in, but rather One Who Beauty is, the Beauty in which all beautiful things participate and the Beauty that, in reality, we all restlessly seek. And when we find this Beauty, it is always too late, since this Beauty is something for which we were made from the first moment of our conception. By the grace of God, Mary, the tota pulchra, the all-beautiful, is the only creature that got it right.

At the time of his death, the American essayist, political philosopher, professor and Catholic priest, Fr. Ernest Fortin is said to have sat up in his bed quite suddenly and remarked, "I see something beautiful." It was a four-word essay, his shortest and last. Surely, it was an essay about the beauty that is God, a Beauty that beckons us in the beautiful?

O Deus pulcherrimus, iube me venire ad te!

Oh God most beautiful, beckon me to come to you!

-----

Andrew M. Greenwell is an attorney licensed to practice law in Texas, practicing in Corpus Christi, Texas. He is married with three children. He maintains a blog entirely devoted to the natural law called Lex Christianorum. You can contact Andrew at agreenwell@harris-greenwell.com.

---

'Help Give every Student and Teacher FREE resources for a world-class Moral Catholic Education'

Copyright 2021 - Distributed by Catholic Online

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

Novena for Pope Francis | FREE PDF Download

-

- Easter / Lent

- Ascension Day

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

St. Catherine of Siena: A Fearless Voice for Christ and the Church

Conclave to Open with Most International College of Cardinals in Church History

A Symbol of Faith, Not Fashion: Cross Necklaces Find Renewed Meaning Among Young Catholics and Public Leaders

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

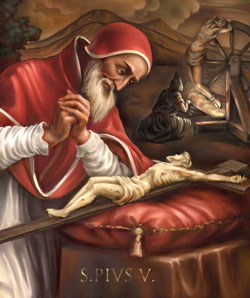

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025- Prayer for the Dead # 3: Prayer of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025