Converging and Convincing Proof of God: The Improbability of it All

FREE Catholic Classes

This probability of the existence of a world capable of sustaining biological life is so improbable as to render the probability virtually nil, especially in a universe that is only 13.7 billion years old according to science. This suggests some sort of intelligent, supernatural intervention had to intervene to even out the odds, to wit, God.

Highlights

Catholic Online (https://www.catholic.org)

12/13/2012 (1 decade ago)

Published in Year of Faith

Keywords: proofs of God, existence of God, improbability, anthropic universe

CORPUS CHRISTI, TX (Catholic Online) - As we discussed in our last article in this series, modern scientists generally acknowledge that, based upon empirical evidence and the principles of astrophysics, the age of the observable universe is 13.7 billion years old. Whether it is or not most of us (including me) do not have the means to know, but let's grant the scientists the premises. This presents modern scientists with a quandary that did no confront those scientists who operated under a regime of Newtonian physics.

It was Newton's view that the universe had existed for an infinite amount of time, and that it encompassed an infinite amount of space and infinite amount of interacting content. Now that scientists have empirical evidence that the universe is not infinite, but rather limited in historical time, one of the most significant arguments that science had against creation has suffered a serious blow.

The issue has to do with the improbability of it all. For everything to have fit together to result in life as we know it is highly improbable. An event that is highly improbable becomes possible, perhaps even likely, if the time during which the improbable act might occur is infinite.

If I have one chance in a million to win the lottery on any given day, it is very unlikely that I will win if I only play a day. However, if I have a one chance in a million to win the lottery on any given day, and I have the chance to play for one hundred million days, it becomes probable that I will win at least once during the span of those hundred million days.

For the same reason, belief that the universe existed for an infinite time allowed for the most highly improbable events to be argued as possible, even probable.

The Big Bang theory--which limited the age of the universe to 13.7 billion years--changed the probability of it all.

To be sure, there is still a long time for highly improbable events to occur. According to Robert J. Spitzer, S.J., given the 13.7 billion years, the total possibilities for interaction of mass energy expressed in minimum units of mass and time is 10 to the 120th power. This, of course, is a huge number, one even unimaginable to us, but it is far, far less than the infinity that Newton and until recently the majority of other scientists thought we had to play the probability game.

Now, the odds against a low-energy universe emerging from the Big Bang (the kind of universe we enjoy, i.e., an anthropic universe) is, according to the Penrose number, 10 to the 10 to the 123rd power.

Compared to the Penrose number, the number 10 to the 120th power is an infinitesimally small number, which means that there is an extreme improbability of our sort of universe arising out of mere chance. In short, it appears that maybe something, or perhaps even Someone, in the famous words of the British astrophysicist Fred Hoyle, has "has monkeyed with physics, as well as with chemistry and biology," and indeed all of existence. There is, it would appear, Mind and Act behind it all.

This is not the proper venue to go over the specifics involved in calculating probabilities. For those interested in the more technical aspects of this, Robert J. Spitzer, S.J.'s book New Proofs for the Existence of God published by Eerdman's is recommended. Briefly, it has to do with an assembly of the improbabilities of a whole lot of improbable requirements that had to be in place for our universe to be the kind of universe that it is.

In those equations that physicists use to describe the physical world, there are what we call universal constants. These are fixed constants based upon the kind of world that we live in, and these fixed constants (which are dimensionless or dimensioned numbers) are what determine the interrelationship between space, time, and energy.

Some examples of these universal constants include the "Planck minimums" of space and time, the speed of light, the gravitational attraction constant, the weak force coupling constant, the strong force coupling constant, and a whole slew of others (Spitzer identifies 20 such universal constants of space and time, energy, individuation, and large-scale and fine-structure constants, though there are more than that).

If these constants fall outside of a very narrow range, what Spitzer says is a "closed range," there would be no universe as we know it. However, the range of possible values that these fixed constants could be is quite a broad, almost infinitely variable range, an "open range," in Spitzer's words.

If any one or more of these universal constants were substantially different from the values they are now, the universe would not be as we know it, and would not be able to support life as we know it and, in probable fact, no life at all. It is in comparing the "closed range" of probabilities required for the universe to exist through its initial stages and its unfolding to the point as we know it compared to the "open range" of probabilities of constants outside this "closed range" that yields, to understate it, a highly improbable number.

This highly improbable number is so improbable as to render the probability virtually nil, especially in a universe that is only 13.7 billion years old according to science. This suggests some sort of intelligent, supernatural intervention had to intervene to even out the odds, to wit, God.

Seven instances of the narrow range of constants is discussed by Fr. Spitzer in his book: (1) the improbability of a low-entropy condition, (2) the interrelationship among the gravitational constant, the weak force constant, and the cosmological constant as it relates to the acceleration and possible collapse of the universe, (3) the strong force constant, in particular in relationship to the electromagnetic constant, (4) the relationship between the gravitational and weak force constants and the neutron-proton mass and electron mass, (5) the relation of the gravitational constant to the electromagnetic constant and the ratio of electron to proton mass, (6) the weak force constant and its relationship to the carbon atom, and (7) the resonances of the atomic nuclei. There are, however, many more.

We cannot discuss all of these in this article, but as a sample of the high improbabilities involved, we can look at the first requirement above, that is, the improbability of a low-entropy condition.

Our world is one of low entropy. However, worlds of high entropy can, at least in theory, exist; in other words, they are probable, and, in fact, more probable in theory than low entropy worlds.

The English mathematical physicist, Roger Penrose, has calculated the odds of our low entropy world compared to all the possibilities of a world other than low entropy and has determined that probability to be 1 chance in 10 to the 10 to the 123rd power.

The Penrose number "is so large," Fr. Spitzer observes, "that if we were to write it out in ordinary notation (with every zero being, say, ten point type), it would fill up a large portion of the universe!"

The probability of this happening by chance is, in short, impossible. And this does not include the improbabilities associated with the other six constant relationships identified by scientists.

To give a sense of what we are talking about, the probabilities associated with our universe having come together by chance in the manner that it did, Fr. Spitzer gives this vivid image. The probabilities associated with the universe having been the result of chance "may be likened to a monkey typing out Hamlet (without any recourse to the play) by random tapping on the keys of the typewriter."

It is unlikely that the monkey would even type out "To be, or not to be, that is the question," much less, "There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy." Both of those questions are on the mind of cosmologists as well as many other humans, though not monkeys even if a dozen of them plinked away on typewriters for 10 to the 10 to the 123rd power days.

In light of the scientific knowledge of the high improbability of the world as we know it existing, the scientist is forced to believe. He may believe that there is an Intellect, God, which he cannot see to explain the improbability of it all, or he may believe--despite the odds--that what he has before him is an incredible, unrepeatable stroke of utter chance.

It seems that the former is more responsible and reasonable than the latter.

In light of the improbability of it all, a large number of physicists have concluded that there must exist a supernatural designing Intellect, one science cannot "see," but one that is implied by the improbability of it all. Other scientists, seeking perhaps to avoid the God question, postulate that, though this universe may be finite and 13.7 billion years old, there may have been a multiplicity of universes, perhaps trillions upon trillions, each of limited time and of which ours is just but one, and so a multiplicity of universes increases the odds that chance could explain it all. There are other theories the scientists come up with to try to avoid looking at the reality that God must exist.

However, in Spitzer's view, this is atheistic desperation, as "[t]here are serious weaknesses in the multiple universe postulate of the weak anthropic principle." For one, there is no empirical evidence for them. What this means is that "there is considerable room for the evidence of contemporary astrophysics to ground reasonable and responsible belief in a supernatural designing Intellect."

It should be observed that the "proof" in this article has nothing to do with the probabilities of biological life and whether natural evolution is, or is not, a probable explanation for biological life that exists (or whether also, the improbability of biological life as we know it existing is similarly so improbable as to suggest that a God is behind it all).

The "proof" we are dealing in this article addresses only the "stage" upon which biological life "acts," i.e., the cosmos, including the world, existing as a whole, one that could support the biological life we have without regard to how that biological life came to be. It therefore has nothing to do with the Intelligent Design Movement which deals with the biochemical and biological aspects of the question of the existence of life, and not the cosmological aspects of the question of the universe that is not hostile to life.

In light of all this, one is reminded of the famous quote by the American astronomer, physicist, and cosmologist, Robert Jastrow: "For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountain of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries."

And beyond the theologians, whose existence, like that of the scientists, is highly improbable, and beyond the mountain, whose existence is also highly improbable, is that Someone who, it turns out is highly probable, and He--Deo gratias--evens out the odds of the improbability of it all.

Thanks to this Someone--Whom we should seek for no other reason than to thank--we are the beneficiaries of this inestimable gift called being!

And if we seek, those with the Faith already know, we shall this Someone find. (Matt. 7:7) Indeed, we shall come to know that this Someone found us first! (Cf. 1 John 4:19) We shall find, even more remarkably, that He pitched a fleshly tent and walked among us, full of grace and truth. And his name was (and is) Jesus. (John 1:14)

-----

Andrew M. Greenwell is an attorney licensed to practice law in Texas, practicing in Corpus Christi, Texas. He is married with three children. He maintains a blog entirely devoted to the natural law called Lex Christianorum. You can contact Andrew at agreenwell@harris-greenwell.com.

---

'Help Give every Student and Teacher FREE resources for a world-class Moral Catholic Education'

Copyright 2021 - Distributed by Catholic Online

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

Novena for Pope Francis | FREE PDF Download

-

- Easter / Lent

- Ascension Day

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

St. Catherine of Siena: A Fearless Voice for Christ and the Church

Conclave to Open with Most International College of Cardinals in Church History

A Symbol of Faith, Not Fashion: Cross Necklaces Find Renewed Meaning Among Young Catholics and Public Leaders

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

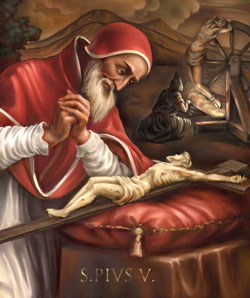

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025- Prayer for the Dead # 3: Prayer of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025