Dear readers, Catholic Online was de-platformed by Shopify for our pro-life beliefs. They shut down our Catholic Online, Catholic Online School, Prayer Candles, and Catholic Online Learning Resources essential faith tools serving over 1.4 million students and millions of families worldwide. Our founders, now in their 70's, just gave their entire life savings to protect this mission. But fewer than 2% of readers donate. If everyone gave just $5, the cost of a coffee, we could rebuild stronger and keep Catholic education free for all. Stand with us in faith. Thank you. Help Now >

Dear readers, Catholic Online was de-platformed by Shopify for our pro-life beliefs. They shut down our Catholic Online, Catholic Online School, Prayer Candles, and Catholic Online Learning Resources essential faith tools serving over 1.4 million students and millions of families worldwide. Our founders, now in their 70's, just gave their entire life savings to protect this mission. But fewer than 2% of readers donate. If everyone gave just $5, the cost of a coffee, we could rebuild stronger and keep Catholic education free for all. Stand with us in faith. Thank you. Help Now >

Converging and Convincing Proof of God: The God of Promises and the Iron Cage of Modernity

FREE Catholic Classes

It was from the human experiences of persons, of communion with the other, of promise, of fidelity and of desire that fidelity not be limited by death that existentialist philosopher Gabriel Marcel, using the illative sense, apprehended, even if only through philosophical hope, that there must be a transcendent reality behind these things: a personal communion with an Other, an Other that is faithful beyond death.

Highlights

Catholic Online (https://www.catholic.org)

12/1/2012 (1 decade ago)

Published in Year of Faith

Keywords: existence of God, proofs of God, illative sense, Gabriel Marcel, Andrew M. Greenwell, Esq, fidelity, promise

CORPUS CHRISTI, TX (Catholic Online) - The Catholic existentialist philosopher Gabriel Marcel might be described as a modern philosopher who was on the lam. He escaped from the confines of modernity's "iron cage," and he did so by the simply expedient of insisting that life was mystery.

As part of this escape from the "iron cage," Marcel believed that the "ontological weight" behind certain words--such as person, promise, fidelity, love, hope--had to be recovered. Such words had become flat--like an airless ball--and had lost their metaphysical bounce. They had to be filled with the air re-inflated with the things of the spirit.

For Marcel, modern man had gotten too comfortable in his "iron cage." He seemed resigned to his prisoner status, and refused to realize that he was in a "false position," that he entertained a view of the world that was not entirely real, and ultimately unsatisfactory because it did not answer the fundamental human questions.

To escape from his predicament, man, in Marcel's view, had to recapture the metaphysical mind that the Enlightenment-era thinkers had suppressed. The current state of affairs simply would not do.

Human thought had to break through the shackles of matter to the truth beyond but unseen. "A mind is metaphysical insofar as its position within reality appears to it essentially unacceptable," Marcel wrote.

Marcel was like the prisoner Edmond Dantès in Alexandre Dumas's story Count of Monte Cristo, unjustly imprisoned in the Château d'If, and who for fourteen years methodically worked on his escape knowing that freedom existed, not "in here," but "out there."

Perhaps of all terms flattened by the Enlightenment philosophers, the term person was the most significant. The word person had become flaccid and lost its metaphysical weight and mystery. This was largely through a shift in the understanding of what it was to be a person. The concept of a person had changed from an ontological concept (something that had to do with being) to a functional concept (something that had to do with having or doing).

This change, and therefore de-mystification of the concept of personhood, appears traceable to the philosopher John Locke, who famously defined the person (the "self") as "a conscious thinking thing . . . which is sensible, or conscious of pleasure and pain, capable of happiness or misery, and so is concerned for itself, as far as that consciousness extends."

All of a sudden, thanks to Locke, a human person was seen only as someone who could think, feel, experience pleasure, and be able consciously to guide itself towards happiness and avoid misery. Having these faculties or functions was what defined the person. Man was no longer a person because of who he is (being), but because of what he had or what he could do (having/doing).

This sort of functional concept lost the full concept of personhood by narrowing it in Marcel's view. It was like poking a hole in a balloon: what was left over was hardly like what it was before it was ruined. And Marcel aimed to regain the fullness of the concept of person through a process he called recollection or recuperative thinking (recueillement). By such process he hoped to regain the mystery that man, as person, is.

In his philosophy, Marcel distinguished between primary and secondary reflection. The primary level of reflection involved our distancing ourselves from the objects of our experience. There is the "I" and there is the "other," the subject and the object. The "I" and the "other" are separated, and the "other" analyzed by the "I" as if it were something entirely separate. While there was some value to this way of thinking, Marcel insisted that the primary reflection cut out a significant portion of reality, one which had to be recovered.

The portion of reality that the primary reflection cut out was that the "I" and the "other" did not live separate lives, abstracted one from the other. Perhaps even more important than the "I" and the "other" of the first reflection--especially where two persons were involved--was the relationship or communion between the "I" and the "other." This was the secondary reflection that had been lost and had to be regained.

While his fellow existentialist Sartre--who famously said that "hell is other people"--entirely overlooked this reality fell into a sort of philosophical solipsism (and also rejected God), it this relationship between persons that was central to the thought of Marcel. For Marcel, the "other" did not represent a hell, but a sort of entry into a metaphysical heaven, ultimately one that suggested that God must exist.

Marcel seized on the incontrovertible fact that human language is full of words that describe relationship between persons--words such as promising, committing, vowing, covenanting, loving. The concepts behind such terms, it seemed to him, contained a reality of their own which imposed themselves on persons. They therefore suggested that there was a reality that transcended us in which these realities participated.

This sort of critical thinking, of course, reached right into the heart of the Enlightenment as if to administer some sort of philosophical CPR. To Descartes' famous first-person-singular cogito, ergo sum-I think, therefore, I am, Marcel emphasized the truth entirely neglected by the father of modern philosophy with the rejoinder: sumus, "we are." The truth was not, in its most important kernel, first person singular, but first person plural.

Reality was not simply what I felt it was (subjectivism) unattached to the world outside of me; reality was not something I possessed for myself, as if it were a drawing I had made and put in my pocket. Reality was also something that we participated in. It was not subjective alone, but, at its most important, inter-subjective, which means it necessarily include the "other."

"A complete concrete knowledge of oneself cannot be self-centered," Marcel wrote in his book Mystery of Being, "I should prefer to say that it must be centered on others. We can understand ourselves by starting from the other, or from others, and only by starting from them."

"Metaphysics," Marcel succinctly said in perhaps the most anti-Cartesian sentence ever penned, "is our neighbor."

In exploring these inter-subjective experiences--especially at their highest level, say in friendship or the love between a man and woman in marriage--Marcel observed that they had to be grounded in promise, and the promise had to be grounded in something beyond promise or it had no meaning.

The goods of communion between persons, such as friendship or marriage, were based upon promise, fidelity, love, and hope. And all these realities suggested an Absolute or they made no sense to Marcel. Without an Absolute Being behind them, it seemed to Marcel that these things were destined to an otherwise inexplicable frustration.

It was the experience of fidelity, and the promise behind fidelity, which led Marcel to transcendence. "The approach to transcendence by way of fidelity proceeds by a meditation on the nature of promising," Aidan Nichols observes in his book A Grammar of Consent when discussing Marcel's thought.

Fidelity to promises is something that is impossible to exercise alone. It is at the heart of a person-to-person communion. As Aidan Nichols puts it: "Fidelity is always a gift to self to another who is at once present to the self and accepted by it as a unique person--in Marcel's favorite word, a thou."

Gnothi seauton, "Know thyself," was writ on the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, a truth which was at the heart of the Socratic philosophy. "To thine own self be true," said Polonius to his son Laertes in Shakespeare's play Hamlet, "and it must follow, as night the day: thou canst not then be false to any man."

Marcel, who, like Shakespeare, was also a playwright, perceived a corollary to the English bard's truth, which, in Shakespearean terms we might put this way: "To the other be true, and it must follow, as night the day: thou canst not then be false to yourself."

This, in a nutshell, was Gabriel Marcel's notion of "creative fidelity." In a stroke of philosophical genius, Marcel flipped the Delphic aphorism "know thyself" (without denying it) to: know the other!

Marcel, however, knew that, among men, death was the ultimate betrayer of fidelity. Death always destroyed communion and spelled certain ruin of fidelity. Our promises do not survive death though we want them to.

But fidelity, especially in its highest form as love, was seen by Marcel as such an important, transcendent value that the only means to vindicate its reality was to suggest the question: Might fidelity survive even death?

In his book Homo Viator, Marcel stated: "It is in this way that fidelity reveals its true nature, which is to be an evidence, a testimony. It is in this way too that a code of ethics centered on fidelity is irresistibly led to become attached to what is more than human, to a desire for the unconditional which is the requirement and the very mark of the Absolute in us."

The very fact that we make promises and honor them, that we can understand fidelity and value it, that we desire that it be eternal, that we want it to survive death, suggests to the philosopher's reason the philosophical hope that this human reality participates in an Infinite Fidelity, the Fidelity of an absolute Other, an absolute Thou. In fine, God.

This gave rise to hope. "Hope," Marcel wrote in his Being and Having, "is a spring; it is the leaping of a gulf. It implies a kind of radical refusal to reckon possibilities, and this is enormously important. It is as though it claimed . . . to touch a principle hidden in the heart of things, or rather in the heart of events, which mocks such reckonings."

This hope mocked such human reckonings by realizing that such reckonings had their limit. Hope sought to transcend reason's limits, and so it was the brother of faith. This sort of hope opens up the prospect of reality outside time, of the existence of an invisible world, and the God behind it all.

"This is what determines the ontological position of hope--absolute hope, inseparable from a faith which is likewise absolute," Marcel wrote in his book Homo viator.

It was therefore from the chain of human experiences of persons, of communion with the other, of promise, of fidelity and of desire that fidelity not be limited by death that Gabriel Marcel, using the illative sense, apprehended that there must be a transcendent reality behind these things: a personal communion with an Other, an Other that is faithful beyond death.

The existence of this Other seems to be what we desire, what we, from a philosophical standpoint, hope for. But are Gabriel Marcel's philosophical reasonings fulfilled?

A Christian of course will answer, "Yes!" Marcel's philosophical hope is satisfied concretely by He, that divine Person with both divine and human nature, who was communion, fidelity, and hope incarnate: the Lord Jesus. Faith in Jesus answers reason's limited reckonings.

Jesus said, "I and the Father are one." (John 10:30) He prayed, in his high priestly prayer, that we may be one "just as we [the Father and he] are one." (John 17:11) He may as well have said, "I am communion." If the Church is anything it is our communion with God the Son made flesh who is in communion with God the Father. Here is the "I' and the "other" together in communion.

Jesus was "faithful to the one who appointed him," (Heb. 3:2), that is God the Father, and so can rightfully ask us to be faithful to God even unto death. (Rev. 2:10). His message is one of faithful love. Here is "creative fidelity" in communion with the Uncreated Fidelity, the Faithful One.

"He is not here," said the angel to the women who came to Christ's empty grave. "He has risen, as he promised." (Matt. 28:6; Luke 24:6). By these words, the angel gave witness to the fact that the God-man Jesus is indeed faithful, and his fidelity transcends even death, since his fidelity broke through the boundaries of the grave and trespassed the limits of time into eternity. Here are promises that transcend death.

This Jesus was Gabriel Marcel's philosophy fulfilled. St. Paul equates Jesus with hope: "Jesus our hope," says St. Paul (1 Tim 1:1). Here is well-placed hope.

Jesus was Person, Communion, Promise, Fidelity, Hope. And, as Life, he overcame death.

Jesus fits all of Marcel's philosophical yearnings for freedom out of the "iron cage" Jesus fits like the right key to unlock the lock in the gate in the prison cell which keeps us from freedom. For it is for freedom that Christ has set us free. (Gal. 5:1)

Jesus is the key which unlocks the "iron cage" of modernity into the freedom and the glory of the Sons of God. (Rom. 8:21)

-----

Andrew M. Greenwell is an attorney licensed to practice law in Texas, practicing in Corpus Christi, Texas. He is married with three children. He maintains a blog entirely devoted to the natural law called Lex Christianorum. You can contact Andrew at agreenwell@harris-greenwell.com.

---

'Help Give every Student and Teacher FREE resources for a world-class Moral Catholic Education'

Copyright 2021 - Distributed by Catholic Online

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

Novena for Pope Francis | FREE PDF Download

-

- Easter / Lent

- Ascension Day

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

St. Catherine of Siena: A Fearless Voice for Christ and the Church

Conclave to Open with Most International College of Cardinals in Church History

A Symbol of Faith, Not Fashion: Cross Necklaces Find Renewed Meaning Among Young Catholics and Public Leaders

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

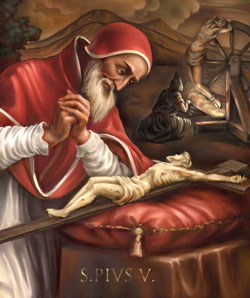

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025- Prayer for the Dead # 3: Prayer of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025