Converging and Convincing Proof of God: Anxiety Without God

FREE Catholic Classes

In this particular "proof" of God, the clue of God's existence is found in the very absence of God in the life of modern man, in the very place where God is declared "dead," and in the metaphysical angst such absence engenders.

Highlights

Catholic Online (https://www.catholic.org)

11/29/2012 (1 decade ago)

Published in Year of Faith

Keywords: existence of God, proofs of God, illative sense, Kierkegaard, Andrew M. Greenwell, Esq.

CORPUS CHRISTI, TX (Catholic Online) - Without question, modernity has presented a challenge to belief in God. The modern world is singularly disenchanted. We live, to use the striking image of Max Weber, in an "iron cage," and iron cage which appears to us as almost a prison where we get no visitors and no news from the outside.

There are various reasons for the modern disenchantment, but one thing that stands out is that moderns have developed such a strong sense of self that it has crowded out the Other. The Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor, perhaps the preeminent scholar of the making of modernity, has amply described the development of this phenomenon in his book Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity.

In any event, with so much emphasis on subjectivity, on interiority, on personal autonomy, and on the concrete individual rather than the objective, the exterior reality, and the universal, modern thought seems focused on man's becoming, and, what is more, becoming on his own terms.

In this view, man does not discover truths about himself and about his own good: he defines his own truth and his own good for himself. "Man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world--and defines himself afterwards," wrote Sartre in his book Existentialism and Humanism.

The focus on becoming whatever one wants and refusing to entertain constraints on what one may actually be is in line with the existential motto: existence precedes essence. This attitude would seem to exclude reference to human nature, to being, especially on that self-subsistent Being, the ipsus esse subsistens, God, who had a hand in creating our being.

Yet even here, in the most hostile perhaps of territories, in partibus infidelium, one can find a means to suggest God's existence. From the ruins left in us by the departure of God from our souls and our societies, we might find a clue. God may be found even among two modern drunks implausibly waiting for Godot, such as we find in Samuel Beckett's play on the absurdity of expecting for help outside ourselves,"Waiting for Godot."

Here the clue of God's existence is found in the very absence of God in the life of modern man, in the very place where God is declared "dead," and in the metaphysical angst such absence engenders.

The existentialist--and, in a way, we are all existentialists now, since modern culture is existentialist--is perhaps best known for his angst, his anxiety. Placed in a world that is absurd--that is, not subject to any reason since there is no God behind it--man suffers anxiety. He does not know his place in the world, and he does not understand himself.

This anxiety is the "uncanny apprehension of some impending evil, of something not present, but to come, of something not within us, but an alien power," as Kierkegaard expressed it in his The Concept of Dread. It is, in fact, the felt absence of God, the "death" of God to the soul. Modern man waits for Godot. And Godot never comes because modern life is disenchanted.

In its extreme form, that anxiety becomes despair. Despair--an emotion that seems unique to man--seems to have no point in a world without meaning, in a world without God.

The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, generally regarded the founder of existentialism, traced the source of this despair to the crisis that comes when man is faced with the gamut of possibilities of who we, as individual selves, might become when we have rejected any objective, external, or universal constraints such as human nature or God. The disproportion between the self to itself--because we had failed to be authentic to self--is what gave rise to this emotion of anxiety of feeling self-estranged, self-alienated.

For Kierkegaard, the existence of despair in modern man was, in the words of Aidan Nichols, a "major clue to deciphering the mystery of our existence," "an important signpost in reading the map of being." In fact, it was a sensation that provided the purchase required to climb back to the awareness of the probability that God exists.

Kierkegaard found this despair to be the byproduct of man as being a "theological self," but denying it. Man, Kierkegaard was convinced, was not what we might call an "autological self." Rather, as a "theological self," man could only find perfection if he recognized God, if he saw himself before God.

Alexander Pope was therefore dreadfully wrong when he wrote: "Know then thyself, presume not God to scan, the proper study of mankind is man." Kierkegaard's great insight was that man cannot know himself unless he stands before God. He must presume God to scan to know then himself.

The way Kierkegaard saw things, three and only three general choices confronted men in response to the anxiety of existence: men could live the aesthetic life, the ethical life, or the religious life.

The aesthete, in its most sensual form, lives for sensual gratification, like the playboy Don Juan. In its most intellectual form, the aesthete lives for intellectual gratification, like the scientist and magician Faust. Ultimately, the aesthetic life leads to a cul-de-sac, an Ahasuerus wandering the world without ever finding meaning and lapsing into romantic irony and despair. Here perhaps we also find Sartre and Camus and their disciples of despair. In a sense, Ahasuerus has landed himself into a temporal hell: the "iron cage."

A step up, but not yet complete, response to life's anxiety is to adopt the ethical life in an effort to give some sort of form to the aesthetic life. This requires a conversion of sorts to a rule, to a committed life. Whereas Don Juan is unstable in his shallow loves, he who follows the ethical life resolves to love one woman and marries.

In the ethical life, some sort of moral standard acts as a sort of lifeline, a golden thread of Ariadne, that takes us out of life's labyrinth where we remain if we follow the life of the aesthete alone. Once the aesthete recognizes the duty to the universal, his life gains some coherence. He is no longer governed by sensuousness and its ephemeral value.

But the ethical life is not enough; it is hideously Pelagian and ultimately self-justifying. It falls short of showing man a clear way out of his anxiety, because man sees in himself what Aidan Nichols in his A Grammar of Consent has characterized as "dragons: malice; the passions; and, above all, the fascinated, Hamlet-like impotence of the individual at the prospect of exercising his or her freedom."

This realization the ethical life's insufficiency leads to the third sphere of existence which presents itself as the ultimate key to unlock the mystery of man's angst: the religious life.

In the religious life, the individual reaches the conclusion, that, to be pulled out from the sloughs of despond, of despair, of disequilibrium, he must confront God and receive God's helping hand. So it was Kierkegaard's conviction that modern man's feeling of angst, of despair, could lead man to God. It was the only way out. Where else to go?

Now, sensing the impossibility of self-extrication and realizing that God might be the only resolution for his quandary presents man with the need for faith. One had to become Kierkegaard's "Knight of Faith." It was the only thing that could sensibly solve man's deep seated anxiety; his alienation from self could only be explained by his alienation from God.

So where do we turn to find God reaching down to us so that we, in turn, may be Knights of Faith?

"God is posited," by Kierkegaard, "in the very act of posing the problem of humanity's self-estrangement; but God's free initiative in our regard belongs not to philosophy but to revelation, which is the divine therapy for the human sickness," says Aidan Nichols.

So reason has brought us to faith's threshold. To overcome angst, we posit God as the only possible remedy. Where do we go to obtain faith in God?

"Our ascent to God via the materials of human experience leaves us inevitably with a question mark that can be removed only by the fresh resources of Scripture and tradition," observes Aidan Nichols, "for they are the rustling of the hem if the Infinite in his personal descent and self-communication to us."

Like the woman suffering from bleeding for twelve years of the Gospel who desired healing from Christ for her malady by touching the hem of his robe (Mark 5:21-43; Matt. 9:18-26; Luke 8:40-56), modern man has suffered from the bleeding malady of angst, and he too must touch the hem of Christ--Scripture and tradition--to have a personal encounter with the Lord.

Like the woman of the Gospels, who spent her entire means on finding a cure in all the wrong places, modern man has wasted his means on false cures for his anxiety, his angst, which have availed him nothing.

Except: since man cannot solve his malady himself, perhaps he ought to turn to Christ? What else is left to modern man, except the healing offered by Christ?

For the woman in the Gospels, that personal encounter with Jesus resulted in the words: "Go in peace and be freed from your suffering." Jesus could just as well tell any modern existentialist, "Go in peace and be freed from your angst."

At Mass we pray: "Deliver us, Lord, from every evil, and grant us peace in our day . . . and protect us from all anxiety as we wait in joyful hope for the coming of our Savior, Jesus Christ."

This is the existentialist's ultimate prayer, if Kierkegaard is to be believed.

As Kierkegaard lay dying at the young age of forty-two, the priest that attended him heard him pray that he would be prevented from final despair. He prayed for the grace of final perseverance. The priest asked whether this hope rested on God's grace in Christ.

"Yes, of course," Kierkegaard answered. "What else?"

Jesus! Indeed. Who else?

-----

Andrew M. Greenwell is an attorney licensed to practice law in Texas, practicing in Corpus Christi, Texas. He is married with three children. He maintains a blog entirely devoted to the natural law called Lex Christianorum. You can contact Andrew at agreenwell@harris-greenwell.com.

---

'Help Give every Student and Teacher FREE resources for a world-class Moral Catholic Education'

Copyright 2021 - Distributed by Catholic Online

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

Novena for Pope Francis | FREE PDF Download

-

- Easter / Lent

- Ascension Day

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

St. Catherine of Siena: A Fearless Voice for Christ and the Church

Conclave to Open with Most International College of Cardinals in Church History

A Symbol of Faith, Not Fashion: Cross Necklaces Find Renewed Meaning Among Young Catholics and Public Leaders

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

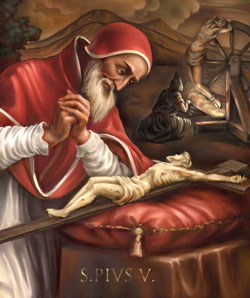

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025- Prayer for the Dead # 3: Prayer of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025