Converging and Convincing Proof of God: The God Behind the Moral Imperative

FREE Catholic Classes

The oughts and ought nots we acknowledge to exist and which are at the heart of our moral sentiment seem to point to a power outside of us to which we are answerable. It is difficult--perhaps even impossible--to explain this sense without tracing it back to some transcendent lawgiver: God.

Highlights

Catholic Online (https://www.catholic.org)

11/23/2012 (1 decade ago)

Published in Year of Faith

Keywords: existence of God, proofs of God, moral law, Kant, Andrew M. Greenwell, Esq.

CORPUS CHRISTI, TX (Catholic Online) - In this series of "converging and convincing" proofs of God, we founded our proofs on human experience-of desire, of truth, of contingency. We used the insights of St. Gregory of Nyssa, St. Augustine, and St. Thomas as our guides in developing these proofs. These sorts of proofs are called a posteriori proofs because they work backwards from experience to God.

Then we looked at St. Anselm's ontological argument, which moved from thought of God to existence of God. This proof did not work from experience, but rather from concept to reality, and so it is called an a priori proof.

Finally, we looked at what might be called introspective proofs--the proof from mysticism, and the proof from an internal assessment of the human condition. St. John of the Cross and Blaise Pascal were our guides.

Now we turn back to another a posteriori proof. This one starts from the experience we have of moral duty. This is the well-nigh universal experience: there are at least some acts that, irrespective of conventional morality, come attached with an ought or an ought not.

To a certain degree, in a world of rampant relativism, this proof loses some of its force as the conventional relativism (currently, the majority report) seems to poison the well of conscience and of duty. Yet even in this most relativistic and pluralistic of worlds, there are still some acts that virtually all seem to agree have an ought or an ought not attached to them.

Rape, adultery, murder, pedophilia, cruelty to animals come with ought nots attached. Most still think that rearing one's children, taking care of one's parents when they are old, and rendering aid to someone in need have oughts attached to them.

Some--we may call them the "Flat-earthers" of morality--still maintain that even these ought and ought nots are the result of convention or emotivism, or should be the matter of utilitarian calculation. But that, to put it mildly, does not seem a very satisfying description of the moral sense. To put it less mildly, it is plain wrong.

At least at its most basic, the moral sense seems to transcend convention, emotions, and even utility. In the words of George Eliot, the sense of duty has something "peremptory and absolute" about it. Those are the words of transcendence.

As Aidan Nichols puts it in his A Grammar of Consent in his understated English way: "We do not feel happy with the idea that values change be changed at will, although were we purely their creators we could in principle change them quite as legitimately and as often as we change our clothes." The experience of oughts and ought nots, he says elsewhere more forthrightly, "has an irruptive quality about it: it breaks in on us from without."

The proof of God based upon the felt existence of moral duty can be looked at from two angles.

First, one can look at this proof beginning from the internal sense of duty and use the illative sense to come to the conclusion that the existence of God is the best explanation for moral duty's existence.

Second, one can look at this proof by showing that without God, there can be no such thing as morality; in other words, the existence of God is the best support for morality.

The oughts and ought nots we acknowledge to exist and which are at the heart of our moral sentiment seem to point to a power outside of us to which we are answerable. It is difficult-perhaps even impossible-to explain this sense without tracing it back to some transcendent lawgiver: God.

"On this view," notes Aidan Nichols, "divine transcendence lies at the heart of our moral awareness, grounds our sense of obligation, and justifies that sense before the bar of reason, preventing it from being a mere unintelligibility in experience, a pure surd."

Immanuel Kant recognized the intimate relationship between morals and God. In fact, because (for complex reasons we won't go into here) he rejected most traditional proofs of God, he found it particularly important to emphasize the link between morals and God.

Kant famously stated towards the end of his Critique of Practical Reason: "Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the oftener and more steadily we reflect on them: the starry heavens above and the moral law within." The moral law, then, shared a certain sublimity, a certain grandeur, which, like the stars, betokened a Creator.

For Kant, morality, which is at heart the life of reason, was essential for human fulfillment, for justice. And yet the idealist Kant was grounded enough to know--even though he only twice left his city of Königsberg--that though we strive mightily for it, justice seem impossible of fulfillment in this life. Justice is simply unachievable. In fact, often (one need only look at the history of Communism) one falls into injustice trying to achieve justice.

Yet, as Kant famously stated, "if justice goes, there is no longer any value in man living on earth." Without justice, there is no meaning to life.

If justice is the demand of moral duty and this is the most rational act and fulfilling act for man, but justice is unachievable, then it seems that we cannot achieve the very thing for which we exist.

In Kant's view, to resolve this paradox, one had to affirm the existence of God.

As Aidan Nichols put the quandary that Kant confronted and whose resolution required the thesis "God exists" to be true: "Either God is or we must dismiss the call to total ethical righteousness, the sense of the sovereignty of the good, as a joke played on us by an unwitting cosmos."

If there is no God, if there is no sense of awe when we look at the stars above and the moral law within, then the stars above and the moral law within are laughing at the cruel joke played upon us.

Our deeply felt need for justice founded on moral truth and reason's mighty suggestion that God exists or (if God does not exist) morality is grounded in a fundamental absurdity guide us into the threshold of faith.

As Pope Benedict XVI has expressed this insight: it is in Jesus that we learn "there is a God, and God can create justice in a way that we cannot conceive, yet we can begin to grasp it through faith. . . . Yes, there is a resurrection of the flesh. There is justice. There is an 'undoing' of past suffering, reparation that set things aright." (Spe salvi, 43).

George Eliot, whom we quoted earlier in this article in part, could not connect the dots. She saw the "dot" of moral duty, but was blind to the connection it had to the "dots" of God and eternal life. As she supposedly told Frederic W. H. Myers in a rainy May evening at the Fellows' Garden of Trinity College in Cambridge: "God, Immortality, Duty . . . how inconceivable the first, how unbelievable the second, and yet how peremptory and absolute the third."

Despite George Eliot's personal desire, stemming from the demons that haunted her, to see morality independent from God and immortality, it seems that without God morality collapses. Is there any doubt that our current moral relativism is founded on atheist premises?

As George Eliot's contemporary and fellow writer, Fyodor Dostoevsky, put it in his Brothers Karamazov in the words of Ivan Fyodorovitch: "For every individual . . . who does not believe in God or immortality, the moral law of nature must immediately be changed into the exact contrary of the former religious law, and that egoism, even to crime, must become not only lawful but even recognized as the inevitable, the most rational, even honorable outcome of his position." Yes, if God and immortality do not exist, then everything is permissible where unprevented by power.

Recently, Pope Benedict XVI has addressed the problem of moral relativism. As we might expect, he comes in on the side of Dostoevsky and against Eliot. "If there is no God, then there is also no moral law." If there is no God, then "[e]veryone comes up with his moral order, in accordance with his own ideas and tendencies."

Implicit in the very notion of the natural moral law is the existence of a divine legislator, the author of man's human nature. Why shouldn't reason make it explicit? Implicit in the very notion of justice is the desire to see it come. Why shouldn't faith--faith in God and faith in the Resurrection and Final Judgment--make it real?

God, Immortality, Duty . . . how necessary the first, how perfectly fitting with our deepest desire for justice the second, and, for this reason, how peremptory and absolute the third.

Our best guide in this regard is the righteous Gentile Job: "With the hearing of the ear, I have heard you" in the peremptory demands of the moral law. "But now my eye sees you" with the eye of reason which tells me that the moral law requires a divine legislator, God.

Therefore let us come to God in the response of faith: "Wherefore I reprehend myself, and do penance in dust and ashes." (Job 42:5-6) Then, and only then, life begins anew and life begins to make sense. The stars above us, and the moral law within us, give us comfort as they testify to the God who made us and who humbled himself, even to the extent of suffering death on the Cross.

-----

Andrew M. Greenwell is an attorney licensed to practice law in Texas, practicing in Corpus Christi, Texas. He is married with three children. He maintains a blog entirely devoted to the natural law called Lex Christianorum. You can contact Andrew at agreenwell@harris-greenwell.com.

---

'Help Give every Student and Teacher FREE resources for a world-class Moral Catholic Education'

Copyright 2021 - Distributed by Catholic Online

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

Novena for Pope Francis | FREE PDF Download

-

- Easter / Lent

- Ascension Day

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

St. Catherine of Siena: A Fearless Voice for Christ and the Church

Conclave to Open with Most International College of Cardinals in Church History

A Symbol of Faith, Not Fashion: Cross Necklaces Find Renewed Meaning Among Young Catholics and Public Leaders

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

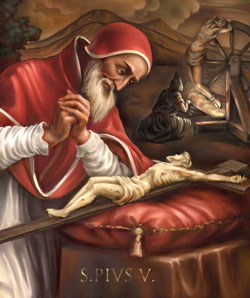

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025- Prayer for the Dead # 3: Prayer of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025