We ask you, urgently: don't scroll past this

Dear readers, Catholic Online was de-platformed by Shopify for our pro-life beliefs. They shut down our Catholic Online, Catholic Online School, Prayer Candles, and Catholic Online Learning Resources essential faith tools serving over 1.4 million students and millions of families worldwide. Our founders, now in their 70's, just gave their entire life savings to protect this mission. But fewer than 2% of readers donate. If everyone gave just $5, the cost of a coffee, we could rebuild stronger and keep Catholic education free for all. Stand with us in faith. Thank you.Help Now >

Converging and Convincing Proof of God: Mystical Encounters with the Absolute

FREE Catholic Classes

Here, then, is the proof of St. John's experience in the words of Aidan Nichols: "Let us take the most repellent human situations and see what comes of them if we approach them as the hidden presence and invitation of the love of God." The "pure" experiences such as these, epitomized in Catholic mystics such as St. John of the Cross, suggest that God is real.

Highlights

Catholic Online (https://www.catholic.org)

11/18/2012 (1 decade ago)

Published in Year of Faith

Keywords: existence of God, proofs of God, mysticism, St. John of the Cross, Andrew M. Greenwell, Esq.

CORPUS CHRISTI, TX (Catholic Online) - Our series on the converging and convincing proofs of God have, in the main, started from our experience of God's creation--whether it be our desire, our sense of truth, the contingency of being--and extrapolated "upwards," as it were, to come to the conclusion that a transcendent God exists. Our observation of creation gave birth to the thought of a transcendent God's existence as a most reasonable explanation for created phenomena. This sort of reasoning takes us to faith's threshold.

In one instance, in St. Anselm's famous if controversial ontological argument, we went a slightly different way. The thought of God as that than which nothing greater can be conceived gave birth to the thought of transcendent God's existence and hence suggested its reality outside the mind.

In this particular article, we are not going to go from the things that are made or from thoughts of the mind; rather, we are going to start from what some have called the pati divina, the suffering of things divine, or, in a word, mysticism. It is a sort of gray area between pure thought and experience of the created world.

Mysticism should not be confused with emotionalism or what Msgr. Knox famously called enthusiasm in the book with that name. Nor should mysticism by confused with religious experience in general. It is something different than emotionalism or enthusiasm or religious experience. It is also something other than mystical phenomena: visions, locutions, levitation, bilocation, or even miracles.

The mysticism we have in mind is the apex of religious experience, to the point where it is almost a religious experience of another kind altogether: it is experienced as a form of an encounter, even a union, with God. Many of us are unfamiliar with this intense form of religious experience, though we perhaps achieve a slight feel of it in ordinary religious experiences, as, for example, we experience pathos at the sight of a crucifix or emotion at the recital of a prayer. But what we're talking about is of another order entirely.

We might take as a working definition of mysticism Fr. Frederick Copleston's definition in his famous debate with the agnostic Bertrand Russell. Mysticism is "a loving, but unclear, awareness of some object which irresistibly seems to the experiencer as something transcending the self, something transcending all the normal objects of experience, something which cannot be pictured or conceptualized, but of the reality of which doubt is impossible--at least during the experience."

Our guide in this dichosa ventura, this blessed venture, of mysticism will be St. John of the Cross, the Doctor Mysticus or Mystical Doctor of the Church. The mystical experiences he had, and of which he wrote in his various poems and commentary on them, is the kind of mystical experience that Copleston defined as "pure," since the experience resulted in a tremendously dynamic and constructive response of love and human perfection which indicates its veridicity. St. John of the Cross's character is, moreover, one of unimpeachable purity and integrity, and he exhibited complete normalcy and sanity, despite intense suffering externally and internally, as a result of these encounters.

Now, there are extreme limitations in relying on religious experience, including the mystical experience, to prove that God exists, and these limitations seriously constrain the value of this proof. But these limits do not entirely nullify the proof. Perhaps the limitations make it, in the words of Fr. Copleston, not a "strict proof of the existence of God." Instead, in light of these limits, the best we can do is to propose God's existence as the "best explanation" of the mystical phenomena in the "pure" sense. It is a soft proof because of its limitations.

We might list some of the limitations.

First of all, not every religious or even mystical experience is sound, much less orthodox. Obviously, the religious experience of men and women do not all point the same way or to the same truth. There is, for example, the great divide between East and West, where mystic phenomena is one between non-Being and Being. We also need to sort out the religious crank, the possessed, the deluded, or those who suffer from hallucinations or psychological abnormalities.

Another problem is that mysticism is notoriously subjective. One may sensibly object: what's in the mind of the mystic does not translate to what is reality, and it is a mistake to go from an internal state to an external reality. Against this we might argue that, though subjective in the sense of witnessed only within, the Church's mystics obviously experience something, an intense experience of the presence and union with the transcendent God himself, and we may consider this experience--despite the dangers of confusing such authentic experience with emotionalism or a misguided enthusiasm or even insanity--as a basis beginning a reasonable inquiry into whether God exists.

The reason for this is that the experience is a subjective experience about something objective, the transcendent Object. It may be reasonable for a blind man to believe what someone with eyes tells him about the world he sees, if he believes that the other person has eyes.

A third objection is that it is most difficult, perhaps impossible, to have a common perception of this mystical experience. Mystical experience is not something like a loaf of bread, something which is outside of us, and the concept of which and the language to identity that concept, is shared in common. And yet, by trying to imagine ourselves in the mystic's place, we might sufficiently understand the subjective state of mystic confronting the transcendent Object identified as God. The experience is not altogether foreign. It is a human experience of the divine.

A fourth problem arises from the inexpressible nature of the experience. The mundane loaf of bread is not ineffable, but isn't the mystic's experience by definition ineffable? Yet we see that despite the ineffable nature of the experience, mystics can describe their experience. So it is not that one can say absolutely nothing about God or the mystical encounter with Him, but rather that one can say nothing absolutely about God and that mystical encounter.

Another difficulty is that we must willing to scrap the empirical reason used in the physical, biological, psychological, and empirical sciences and rely on a broader illative sense or what the medieval theologians called intellectus. If we insist on attributing mystical experiences to chemical effluvia in the brain, or self-induced hypnotic states, or a "God gene," or some such natural explanation, similar to what Henry James did in his famous Varieties of Religious Experience, this proof will yield nothing at all.

We have to be willing to expand our way of thinking beyond that of the materialistic Horatio and least accept the possibility that "there are more things in heaven and earth . . . than are dreamt of in your philosophy," as Shakespeare put in the mouth of Hamlet.

Finally, how can a mystic's experience be evidence of God if the mystic, at least if a Catholic mystic is at issue, already believes in the reality of God? In other words, the mystic's faith cannot be the basis of reasonable evidence because the experience is already informed and interpreted by faith, and so is not a naked experience.

But this last problem can be surmounted by what Aidan Nichols in his A Grammar of Consent calls "two moves." The first is to recognize that the mystic's experience is, to some degree, autonomous or in "creative rupture" with the religious tradition, and so give rise to and "additional experience." This "additional experience" of the mystic can provide a basis and demand a response even from those who do not (yet) believe.

When it comes to this "proof," the believer is at an advantage apologetically. A mystic, such as St. John of the Cross, will have an "additional experience" of God's existence. There is no analogous experience available to an agnostic or an atheist. An agnostic or atheist can never point to a mystical experience of God's nonexistence as a real object that draws him into an intense love and bliss.

Importantly, St. John of the Cross's mystical encounter with God was something that seemed completely unattached to his external world and his internal world, wherein all evidence indicated God's absence. All external evidence of God's existence, of God's providence, was absent to St. John when he was imprisoned in the darkness of a dank, foul, dark 6 X 10 foot prison cell in Toledo, suffering from dysentery, lice, and under the threat of being executed. Internally, St. John of the Cross suffered from a tremendous dryness. Emotionally, he felt the emptiness of nada, nothingness. For him it was dark within and dark without.

It was in these absolutely unconducive circumstances, suffering the want of any and all external and internal support, that St. John found the superlative invitation of divine love," el divino extremo, the "divine extreme." God alone! Solo Dios basta!

Aquésta me guïaba

más cierta que la luz del mediodĂa,

adonde me esperaba

quien yo bien me sabĂa,

en parte donde nadie parecĂa

It lit and let me through

More certain that the light of noonday clear

To where One waited near

Whose presence well I knew,

There where no other presence might appear.

Here, then, is the proof of St. John's experience in the words of Aidan Nichols: "Let us take the most repellent human situations and see what comes of them if we approach them as the hidden presence and invitation of the love of God." The "pure" experiences such as these suggest that God is real.

St. John of the Cross did just this, and "the triumphant survival of his humanity through a personal holocaust," as Aidan Nichols describes it, bore fruit in his poetry and prose, and especially in that poem, "The Dark Night." "The existence of that poem, written in that place," is itself theistic evidence," suggests Nichols.

More contemporaneously, St. Maximilian Kolbe did a similar thing, and "the triumphant survival of his humanity through a personal (and even more literal) holocaust" bore fruit when he never doubted God amid the horrors of Auschwitz, and willingly exchanged his life for one of his fellow prisoners--a father with a wife and children--in an act of great love. The self-giving of St. Maximilian Kolbe, in that horrible and repellent place, is also theistic evidence.

Even more modernly, François-Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan, Archbishop of Saigon (later Cardinal), who was detained for thirteen years amid the horrors of a Vietnamese re-education camp, nine of which were in solitary confinement, nevertheless remained unshakenly convinced in God.

As Pope Benedict XVI, who mentioned him in the encyclical Spe Salvi, stated: "During thirteen years in jail, in a situation of seemingly utter hopelessness, the fact that he could listen and speak to God became for him an increasing power of hope, which enabled him, after his release, to become for people all over the world a witness of hope--to that great hope which does not wane even in the nights of solitude." Yes, the dedication of Nguyen Van Thuan and his witness to God is also theistic evidence.

In the likes of these "pure" experiences, when God is experienced in the most unlikely and repellent places and without semblance of internal psychological or emotional support--and the Catholic Church has a plethora of them to which it can point since its altars are full of saints and they multiply each and every day--that we find theistic evidence.

All of these "pure" experiences have their source at the Cross, where a Jew who claimed to be God, was scourged, nailed to a cross, and abandoned--so it seemed--by both God and man. And yet, here at Calvary, in the most implausible of circumstances, when God seemed to all most distant--Eloi, eloi, lama sabacthtani, My God, my God why have you abandoned me--that the Lord's glory and the Lord's love revealed itself in the most invisibly true and pure and most intense way, like the hottest of flames.

For the penitent thief, Jesus Christ on the Cross was theistic evidence. Jesus! God! If we could have the penitent thief's spiritual eyes!

The existence of the Christ's Sacrifice on the Cross, lifted in the place of Golgotha, the place of the skull, and repeated bloodlessly on Catholic altars, is itself theistic evidence. Its veracity is mercifully confirmed in the Resurrection, as perhaps the Cross would have been too much naked reality for man to believe true without it being clothed and confirmed by the historical miracle of Christ's Resurrection.

This sort of proof converts. St. Teresa de JesĂşs (also known as St. Teresa of Ăvila) was another mystic soul with these "pure" experiences, and she, like her Carmelite reforming cohort, St. John of the Cross, wrote about her mystical ascent to God and her encounter with Him.

The moment that the Jewess intellectual Edith Stein read about the mystical experiences of St. Teresa in the latter's Autobiography (which she happened to read quite by "accident") she knew that God as described by St. Teresa existed.

As Aidan Nichols summarized Edith Stein's thought process in his A Spirituality for the Twenty-First Century, Edith Stein concluded: "If Teresa is real, then God is real."

We can say the same for all "pure" souls: "If St. John of the Cross is real, then God is real." "If St. Maximilian Kolbe is real, then God is real." "If the Servant of God Nguyen Van Thuan is real, then God is real." Beginning with St. Dismas, the penitent thief, and on and on . . . .

All these "pure" souls recognized the Truth made Flesh, loved Him, and made Him the driving force of their lives. It is this which gives them their superlative attractiveness, resulted in oustanding integrity, and which makes them proofs of the existence of the God to whom they gave themselves with such abandon in the circumstances of seeming abandonment: If Jesus is real, then God is real.

-----

Andrew M. Greenwell is an attorney licensed to practice law in Texas, practicing in Corpus Christi, Texas. He is married with three children. He maintains a blog entirely devoted to the natural law called Lex Christianorum. You can contact Andrew at agreenwell@harris-greenwell.com.

---

'Help Give every Student and Teacher FREE resources for a world-class Moral Catholic Education'

Copyright 2021 - Distributed by Catholic Online

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

Novena for Pope Francis | FREE PDF Download

-

- Easter / Lent

- Ascension Day

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

St. Catherine of Siena: A Fearless Voice for Christ and the Church

Conclave to Open with Most International College of Cardinals in Church History

A Symbol of Faith, Not Fashion: Cross Necklaces Find Renewed Meaning Among Young Catholics and Public Leaders

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

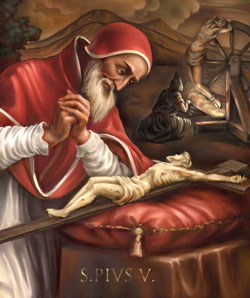

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Daily Readings for Tuesday, April 29, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025- Prayer for the Dead # 3: Prayer of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Daily Readings for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

St. Pius V, Pope: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Prayer to Saint Joseph for Success in Work: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, April 30, 2025 St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025

St. Catherine of Siena: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, April 29, 2025